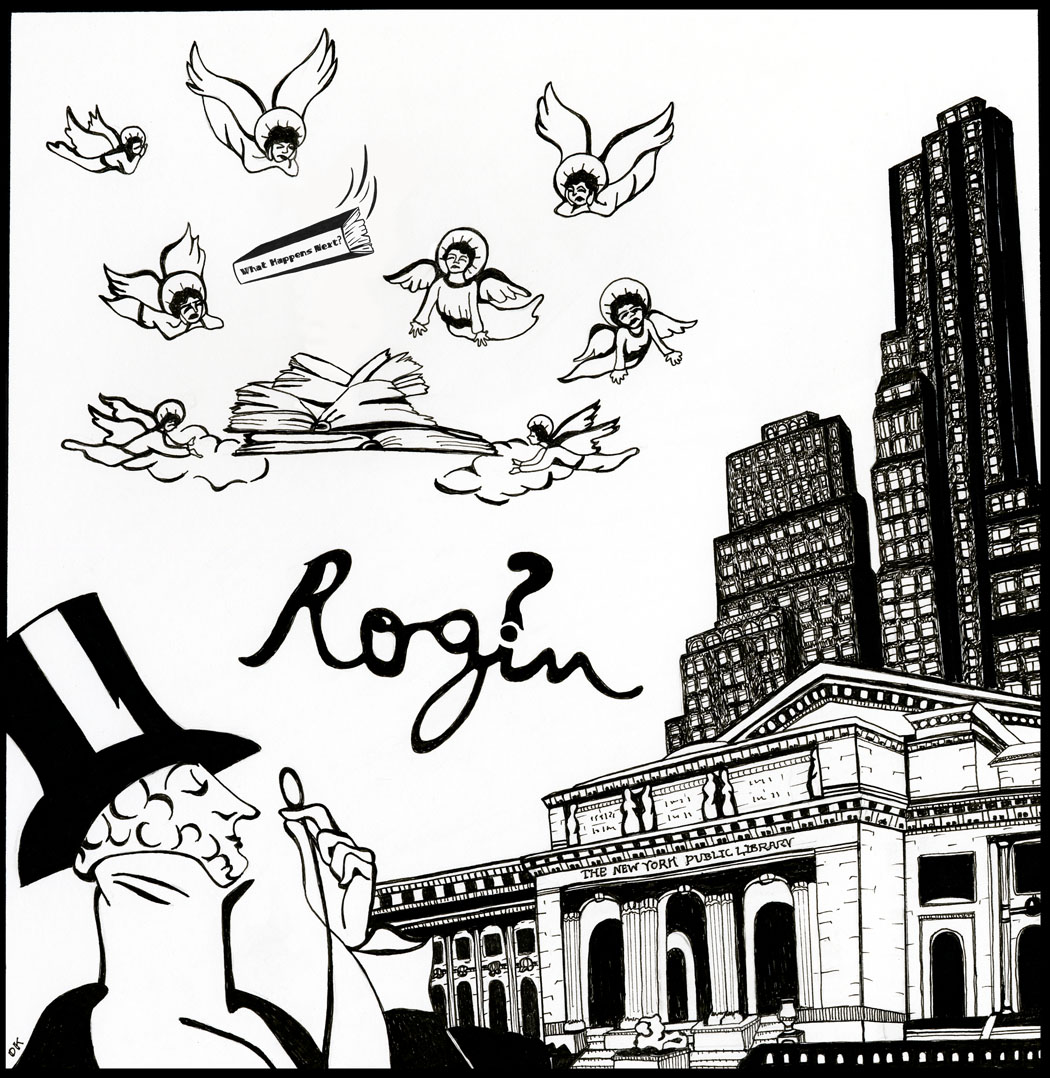

HIDDEN CITIZEN:

Rediscovering the brilliant, funny novels of Gilbert Rogin

[Article and illustration from Lowbrow Reader #7, 2009, and The Lowbrow Reader Reader book, 2012.]

Reviewing Gilbert Rogin’s novel What Happens Next? in Partisan Review in 1973, Joyce Carol Oates wrote, “Because Rogin is…very funny his work is in danger of being underestimated….” To make a Roginesque joke, his work has been so widely underestimated, it might take a metaphysician to prove its existence. Each of his three books — a collection of stories, The Fencing Master (1965), and two novels assembled mostly from published stories, What Happens Next? (1971) and Preparations for the Ascent (1980) — went out of print in short order. His deaccessioning from the public libraries of America has proceeded apace, so that many of the copies available on usedbook aggregator Bookfinder.com are “ex-library.” Nor are any extant in the New York Public Library’s circulating branches — in his native city where his work is set! A

lonely one copy each turned up in the NYPL’s noncirculating CATNYP database, along with the plaintive software query to my “Gilbert Rogin” search, “Do you mean ‘gilbert groin’?” (I think Rogin would appreciate that anagrammatical query, since he both anatomizes libidinal adventures and plays inventively with language.)

lonely one copy each turned up in the NYPL’s noncirculating CATNYP database, along with the plaintive software query to my “Gilbert Rogin” search, “Do you mean ‘gilbert groin’?” (I think Rogin would appreciate that anagrammatical query, since he both anatomizes libidinal adventures and plays inventively with language.)

Of course, most writers suffer the fate of obscurity, but most have not had such an enviable literary career. Between 1963 and 1980, he published 33 stories in the New Yorker and others in Esquire, Harper’s and Vogue; he won an Academy Award for literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (in 1972, along with Harry Crews, Paula Fox and Thomas McGuane); and his novels have received high, sometimes rapturous, praise in reviews. Besides Oates’s lauding of his “unique vision” in What Happens Next?, Anatole Broyard, the New York Times‘ primary reviewer, found the book’s “sardonic dialogue” superior to Donald Barthelme’s and its portrait of marriage on a par with John Updike’s Maple stories. Poet and critic L.E. Sissman, writing in the New York Times Book Review, declared at the outset of his review, “I think Gilbert Rogin has written a great novel, the first one I’ve run across in quite some time.” Nine years later, his next and last book, Preparations for the Ascent, received less attention, but Mordecai Richler, admitting in the Times Book Review that he was not familiar with Rogin’s work, found it “subtle, original, and refreshingly intelligent.” And in his 1979 introduction to Polish novelist Bruno Schulz’s Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass, Updike himself — after comparing Schulz to Kafka and Proust — invoked one of Rogin’s New Yorker stories, linking the two as “writers in a world of hidden citizens” who “work with an excited precision, pulling silver threads from the coarse texture of daily life.”

It was in that canonized company that, recently happening upon Updike’s essay in his collection Hugging the Shore, I first heard of Rogin’s fiction. His name, however, I knew well. When I started working as a reporter at Sports Illustrated in 1987, Rogin had recently departed as managing editor, the magazine’s top post, after a 30-year career there, and his name still echoed in the halls. He then moved to the science magazine Discover and later to a lofty Time Inc. corporate editorial position, from which he retired in 1992. (Among other accomplishments, he helped Quincy Jones found Vibe.) Updike’s anointing sent me to my Complete New Yorker DVD, where I found Rogin’s stories, before later seeking out his books from the above-mentioned used-book site.

The questions that pricked me amid the amassed encomiums were “How does such a lauded writer disappear so thoroughly?” and “Is he really worthy of resurrection?” Or, to put it in another anagram of his name, “Lit gig reborn?” I wondered if Rogin, born in 1929, might be a male analogue to Paula Fox, six years his elder, whose out-of-print oeuvre in adult fiction had been revived by a Jonathan Franzen essay declaring her novel Desperate Characters to be “obviously superior to any novel by Fox’s contemporaries John Updike, Philip Roth and Saul Bellow.” I doubt I’d venture that far into hyperbole, but could Rogin, like Fox a chronicler of New York City angst, have been unfairly overshadowed by better-known peers?

I worked backward from the most recent book, ending with the short stories, which, while skillfully rendered, seemed to be a warm-up for the two novels. Those books essentially comprise one long narrative of a marriage and its entropic dissolution; Julian and Daisy in What Happens Next? become Albert and the similarly floral Violet in Preparations for the Ascent, and the later book largely picks up in chronology where the other one ends. (Strangely, in the latter, Rogin doesn’t change the name of the wife’s wastrel ex, Skippy Mountjoy, or those of the family dachshunds, Josh and Jake.) The protagonist, no matter the name, is a (presumably autobiographical) middle-aged, Jewish, Manhattanite male, a magazine writer of eclectic intellectual interests and eccentric habits. If Stendhal defined the novel as a “mirror being carried down a highway,” Rogin’s carrier stares at himself in the mirror while lugging it up West End Avenue to his therapist’s office or to Madison Square Garden for a basketball game. He moves from place to place in accord with his daily duties as husband and son, lover and friend (and only rarely as employee), hilariously hyperobservant of the world around him while pondering his “immobilized,” abstracted personality (“the Apollonian and Dionysian sides of character being of equal strength”). “The trouble with you, Julian,” his wife tells him in What Happens Next?, “is that you have no outer life.”

Rogin’s dialogue is often slightly stylized, which heightens the humor. In Preparations for the Ascent, Albert, separated from his wife, moves mere blocks away and can see her building from his.

“Oh, God,” his mom had said when Albert told her where he had

moved. “You can hear her hair dryer from there. Couldn’t you have

put more ground between yourselves?”

“It wasn’t premeditated,” Albert said. “It was a supervenient turn of

events. If you visualize the marriage as a ship that has broken up, you will

see us as two shipmates clinging to opposite ends of a large piece of flotsam.”

“I see you as two idiots awash on a delusion,” his dad said.

There are echoes of Woody Allen in both the heady nature of the jokes and the slapstick of what little action actually does occur. He bangs heads with his dachshund; he extricates his stepson from the locked bathroom by delivering “a well-aimed kick at the doorknob, remembering — ah! too late — that he is barefoot”; he demonstrates to his wife the most efficient route to answer the telephone in the living room from the bedroom — “if you take the first turn a little wide, you’ll be able to negotiate the second without

decelerating. Please observe.”

But there’s much more than jokes and pratfalls going on here, as we are reminded on almost every page by the fineness of observation. His descriptions

can be beautifully lyric (a New York sky that’s blue “like the air in which Giotto’s lamenting angels hover”); slyly critical (a Southern California hotel room so “grandiose” it looked “as though it had been built and furnished with an eye to the future, for the race of giants we would become”); and poignantly tactile (he remarks of his dachshund Josh, linking him with his

stepson, Barney, and wondering if he’s neglected them both, in an efficient, lovely elision: “How old and scruffy he is, like Barney’s football, which had been kicked around the P.S. 41 schoolyard for years.”)

Pinpointing why an author fails to find his audience is largely speculation, but perhaps Rogin’s problem was timing. He was writing at the very apex of the market for protagonists who were middle-aged, Jewish, Manhattanite male intellectuals/writers and musers. The urtext in this genre is Saul Bellow’s Herzog (1964), with cohorts Mailer, Malamud and others doing variations on the theme. In October 1971, the same month What Happens Next? appeared, the influential critic Morris Dickstein identified “many years of imitation and, finally, glut in Jewish writing,” and Dwight Macdonald, in November of that same year, declared Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) “the Jewish novel to end all Jewish novels (which it unfortunately hasn’t).” Even as WASPy a writer as John Updike satirized the genre and its practitioners in Bech: A Book in 1970, which appeared on the National Book Awards shortlist with Bellow’s Mr. Sammler’s Planet. In 1980, Preparations for the Ascent had the bad luck to enter a cultural world which had just the year before feted the works of similar, better established writers in his same vein: Malamud’s Dubin’s Lives and its inventively musing libidinal biographer, Roth’s The Ghost Writer and its fantasizing historical revisionist Nathan Zuckerman, and even Woody Allen’s Manhattan. A cursory glance at Rogin could have convinced us that we’d heard it all before.

What unifies Rogin’s novels is voice and humor, but some critics of the day were flummoxed by his “inaction” heroes and the lack of a traditional plot or character development. A reviewer in Philip Rahv’s journal Modern Occasions griped about What Happens Next?, “Mr. Rogin seems … resigned to recording the nonevents in Singer’s life.” In New York magazine’s review of Preparations, novelist Evan Connell wrote, “[From Albert's] behavior you can hardly tell where he is or what he is doing. Nothing changes.” Even Richler admits about Preparations, “…though I both enjoyed and admired it, and even laughed out loud more than once, I’m not sure I understood it” before asserting, “I’d rather be baffled by Gilbert Rogin than read a story made plain by many a more accessible but predictable writer.”

Read today, Rogin’s books seem fresh, the author possessed of a turnof-the-21st-century comic sensibility more than a fundamentally Jewish one similar to his peers from the 1960s and 1970s. Obsession, and particularly self-mocking self-obsession, rather than neuroses per se are what characterize his protagonists. The criticisms above — that Rogin is merely recording nonevents or that nothing changes in his books — are identical to descriptions of Seinfeld. And it’s no stretch to imagine Seinfeld mastermind Larry David in his current show, Curb Your Enthusiasm, holding, as Albert does, an “operative number” of 32, by which he finds “patterns” in his life, to the point that he performs actions in its multiples — sit-ups, pages read, even executing 128 strokes while making love to his girlfriend (“‘I can see you moving your lips,’ she says midway”).

Furthermore, Rogin’s experiments with narrative and self-reflexive techniques anticipate strategies adopted by the contemporary literary generation. The late David Foster Wallace’s fondness for footnotes finds an ancestor in one chapter of What Happens Next?, when Julian uses them to record his parents’ reactions to the story he’s written about them. The result is a Russian doll of a read, in which he unpacks age-old parent-child anxieties while questioning narrative reliability, almost sentence by sentence. A later chapter relates an argument between Singer and Mountjoy almost entirely in police-report diction (“Singer inquired of Mountjoy who the hell he thought Singer was”), studded with excerpts from their grade-school comment cards. Other chapters feature diagrams (lunch-table accouterments as chess pieces), mathematical formulae (calculating the point C at which his and his psychiatrist’s sightlines would meet), Heartbreaking Genius-like references to the book itself (“Regard it here in eleven-point Baskerville”), and numbered lists (“The bad things that happened on their vacation…”). Rogin’s work, it seems to me, deserves that most clichéd of compliments: ahead of its time.

More evidence resides in the first pages of What Happens Next?, from a story originally published in 1966, in which one of Singer’s TV-producing cronies envisions a game show in which a celebrity panel has to guess the problem a contestant faces (“I’m in love with a woman, but I think she’s after my money”) then “give the contestant two, three minutes personalized advice and comfort.” The producer says, “We’re liable to come up with television’s lowest ebb.” Perhaps not even Rogin could have envisioned Big Brother, but the show he conceived would fit into today’s lineup nonetheless.

In the end, Rogin’s books deserve to be read and reread for one simple reason: They’re funny. Along the way, feel free to be wowed by his pinballing imagination, his linguistic dexterity and his masterly ability to see clearly what is right in front of our faces but unnoticed until he pointed it out.

And what happened next to Rogin, after Preparations? Why did we not get a continuation of the story past middle-age and into dotage? In About Town, his 2000 history of the New Yorker, Ben Yagoda sums up Rogin’s literary fate in, appropriately enough, a footnote: “Soon after publication of [Preparations], Rogin submitted two stories to [Roger] Angell, who told Rogin he was turning them down because they seemed to go over familiar ground. The criticism had a shattering effect on Rogin, and subsequently he has written no fiction.”

—Lowbrow Reader #7, 2009

(The article also appears in The Lowbrow Reader Reader book)

Illustration by Doreen Kirchner

See Lowbrow Reader #7 and The Lowbrow Reader Reader for “My Masterpieces” — the first Gilbert Rogin story to be published since 1980. See Verse Chorus Press for a new single-volume edition of What Happens Next? and Preparations for the Ascent.