Blow It Up: Bill Morrison, the Balloon Man

[Article and illustration from Lowbrow Reader #10, 2017]

In 1971, Bill Morrison, the Balloon Man, recorded a series of one-minute vignettes. Surreal and impressionistic, these were artless works of art, each monologue topped and tailed by an upbeat horn-and-banjo tune. Unheard in their era, in 2004, the recordings were released as a limited-edition CD, The Balloon Man: 40 One Minute Bio-Vignettes by Bill Morrison. Issued by SharpeWorld—a label primarily associated with the absurdist ’60s comedy duo Coyle and Sharpe—the album plays like Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music verbalized as one man’s mental breakdown. This is the sound document of a prop comic’s fragmented treatise. It opens with “Blow It Up”:

Now, when you have a balloon, blow it up

Place it in your mouth and blooow

Ya know, that’s what you do

I know that some of you are going to have some trouble doing this

At first, you’re not going to be able to get that far

You won’t be able to blow up a balloon at all

Hey, hey, hey, hey, hey, hey, hey, hey!

Don’t worry, it’s a natural thing, ya know

It isn’t only peculiar to you, just keep on trying

Remember, remember, remember that Rome wasn’t built in a day

With somebody—without somebody, rather—getting hit on the head by a brick

But that didn’t stop them from going outside and having an orgy if the weather was nice!

In the early ’70s, the recordings had been pitched to radio station directors. But these monologues were hardly the sound of the counterculture comedy then in vogue—they could never connect with listeners in the manner of a Carlin, Klein, or Pryor. Morrison’s rambling was an interior monologue externalized. As a listener, one is not always sure that it is even funny; to hear it feels like eavesdropping. The speech is murky, characterized by the self-referential angst that runs through all of Morrison’s work.

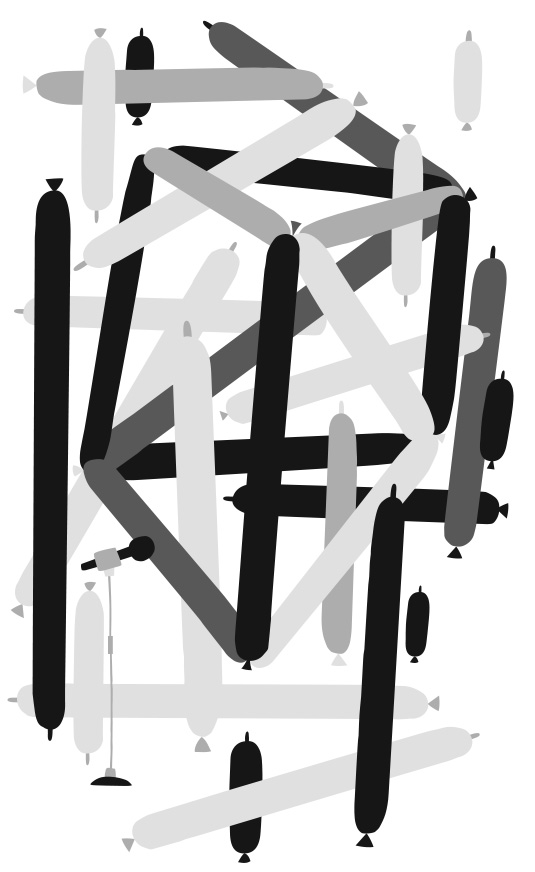

The Balloon Man had his fans, just enough to qualify as a cult act. Few in the business who saw his act knew what to make of it—but then again, neither did Morrison himself. By his own admission, his act was often loose, sometimes ramshackle. He would walk onstage and, in a deadpan voice, begin to explain his “balloon structures.” He spoke of the mundane humiliations of working supermarkets, circuses and carnivals, and how he aspired to artistic expression with his balloons rather than making mere animal shapes. As he blew up the balloons and bent them into shape, Morrison’s speech would descend into the absurd, carried by a sonorous voice that could credibly sell insurance, but would crack and fall into the depths of a latex gestalt therapy session. It was personal purgatory filled with balloons.

“I was doing myself looking for myself as I was doing it,” Morrison tells me. He writes this in an email—one of several we exchange over a six-month period, during which my inbox fills with words twisted like origami dragons. “Peculiar, eh,” he continues. “All the time as me, Bill Morrison, developing an act. That was the prime thing, wasn’t it? The act.”

Morrison was born in Portland, Oregon, decades before cool descended upon the city. In his 20s, he graduated from Air Force navigator school in Texas, then returned to the Northwest. All the while, he thought of being funny, working out how the ideas that would worm their way through his head could be tamed into an act. He took a gig as a presenter on KIHR, a radio station in Hood River, east of Portland, but was fired after he decided to read the phone book on air. He took this as his cue to head for Los Angeles, arriving in 1959.

By 1963, Morrison had corralled the ideas in his head into what approximated an act. While holding down a day job as a car salesman, he hustled for spots in clubs like the Ice House, operated by Bob Stane in Pasadena, and the Troubadour, in West Hollywood. “No balloons then,” he says. “Button down. A sport coat or suit and narrow black tie, Johnston & Murphy shoes that were never scuffed. It was all memorized and set material. As I say, a bit offbeat. I wrote it or got it, bought or lifted from sources. At first, I got up everywhere I could, did USO Shows, veteran hospitals. It was the folk era dominating the clubs. Folk rooms were where I worked, mostly for change.”

It was around 1968 that Morrison made balloons part of his act, participants in his cracked Socratic dialogues. He wasn’t the only comic using them. A young Steve Martin famously employed balloons, following the example of his early hero Wally Boag (another Portland native), who performed in the Disney stage show the Golden Horseshoe Revue.

In 1972, Johnny Carson relocated The Tonight Show to L.A., which led to a stampede of comics heading west. At this point, Morrison had been at it for what seemed like ages, playing folk clubs and even getting the occasional TV slot from Steve Allen—an ardent fan who referred to Morrison as “the original Steve Martin.” But by the early ’70s, Morrison was tired of his act, and no longer up for the fight. As he continued working, the competition grew stiffer and spots harder to come by. Approaching 40, he was unable to muster the enthusiasm to blow up a balloon and wax poetic about, say, Margaret Mead or “sex between the big toe.”

The next few years were fallow, as Morrison’s fortunes waned while those around him went on to bigger things. He was still struggling to hone his act into a palatable, digestible “delivery system” for his stream of balloon consciousness. “Show business is show business. Meaning you’ve got to have an act,” Morrison says. “But of course, you have to have a structure aside [from] just personality if you want to be in show business: a delivery system.”

The act had become an elusive concept for the Balloon Man. Either by what he calls “laziness” or some deep-seated refusal to buckle to the strictures of structure, he set about making the essence of his act the destruction of the idea of the act. Two decades after arriving in Los Angeles, his standup career on life support, Morrison no longer cared to craft a “finished show business product” for popular consumption. He set about pushing further into the gray zone of comedy as performance spectacle, drifting into freeform monologues that tread close to the line of deliberate bombing.

In 1979, the comedian began The Mister Morrison Show, a public access program that would run in Los Angeles for three decades. Given free rein, away from the pressure of performing before a live audience, Morrison used the creative visual elements of TV to explore his non-act, the balloons still part of the experience. “The audience for the most part was not mainstream,” he says. “They were looking for something different and not mainstream itself. I fit that bill.” Supposedly, George Carlin was a Mister Morrison fan, taping the show and sending copies to friends across the country.

Along with producing Mister Morrison, during the late ’90s and early 2000s, Morrison published a zine, Balloons and Patter. The publication showcased his poems and short stories, as well as occasional recollections of misadventures with his friend Craig T. Nelson (he of Coach fame). The stories have a surreal bent familiar from the show’s monologues and kindred titles: “Bob’s Big Boy Cruise Romance,” “Punks in the Polo Lounge,” “Pop in the Speedway Shortcut.” Dense with wordplay, they feature high ideas grubbing about on grimy, sun-soaked L.A. boulevards.

Morrison began his journey tied to the conventions of genre and performance, which made sense if his caper was going to amount to anything in terms of career. But it never added up. From the time he read a phone book on air as a young radio announcer, Morrison displayed an intuitive sense of outsiderness, suggesting that he could never stomach being a straight comedian, even in the orthodox alternative realm. Merely to entertain such folly was, to him, the biggest joke of all. As he shunned any notion of show business success, he drifted further into his head. The solace he found in DIY platforms pushed him to the fringe in his era. But in the current age of art television—at times delivered with little or no network backing—his autonomy and unapologetic weirdness seems practically mainstream.

Morrison, now in his mid-80s, still lives in Hollywood. He still performs, too, mainly with a local a cappella group, Las Palmas Players. “Do what I do do as if it is important and has worth in itself,” he writes me. “And feeling the same exact barbs and arrows, slings, slings and dubious joy of engaging to prove a point of conviction as I did 50 years ago.”

Six decades on the margins of show business and Bill Morrison is still not sure who Bill Morrison is. Who is this Balloon Man, and what is his act? The only thing he seems to know for sure is that it’s what he does. “Don’t let nobody or nothing get you down about yourself and expression for long,” he claims. “That is what kept me silly after being down about how bad I am received sometimes. It is worth it just doing it.”

“Well, sure, I want to get ahead,” begins “Bleeding Salmon,” a cut from The Balloon Man:

I don’t know anybody who doesn’t want to get ahead in something, some ways, somehow

In something that’s particularly important to him

I know that I do

And certainly as I’m doing it, why I see that I can see myself in the image of ambition

And I watch every move I make

Reflecting on the right way to pick my nose during an intelligent conversation with a bleeding salmon, sterile over a billion ball bearings

And so I guess I know pretty much

As I look at myself there that—oh gosh!

I just see that reflection of all of those nickels that I could have won for every doggone ball that I’ve ever dropped

—Lowbrow Reader #10, 2017