Gilbert Gottfried, New York Punk

In 1987, Gilbert Gottfried made his debut appearance on Howard Stern’s radio program. Although it went unspoken, the host and his guest had somewhat overlapping lives. Both men were in their early 30s and clinging to the fringes of show business. Both were Jewish nerds who had come of age as outsiders in rough patches of New York: Stern in a predominantly black area of Long Island; Gottfried in pre-chic Brooklyn and the East Village of burning tenements and open-air heroin bazaars. They found escape and salvation through the junky pop culture of monster movies, super heroes, rock & roll, and comedy. And while both performers’ acts had roots in the ’70s, their entry to comedy’s major leagues began at the dawn of the ’80s, when Stern paired with his invaluable on-air foil Robin Quivers and Gottfried started his short-lived—and little-remembered—tenure on Saturday Night Live.

The Howard Stern Show in its modern-day incarnation is deliberately paced and nearly intellectual in its majestic pursuit of idiocy. Whether involving showbiz royalty (Jay Z, Jerry Seinfeld) or side-show freaks (an oddly well-spoken man with a 132-pound scrotum), interviews unravel methodically—deep probes with a therapeutic air. Yet in its adolescence, before Stern had his in-built satellite audience or the mantle of celebrity, his show was hyperactive and tense, like New York City. The maiden Gottfried interview is particularly berserk. To hear it is to tumble into the pages of an old MAD magazine or the dinner table of Minnie Marx.

Although at the time of the appearance Gottfried seemed to be living with his mother, he was nonetheless a larger national star than Stern, who was still gaining a foothold in New York. As the comedian, who appears unfamiliar with the show, enters the room, the radio host confesses to nerves. Gottfried is “so wacky,” Stern notes, “I’m really wondering how this interview’s gonna go.” As a straight interview, it flops. Like many comedians, Gottfried seems unwilling—and possibly unable—to advance a conversation in the manner traditionally favored by human beings. Instead, he cracks wise at any available opening. At one point, Quivers attempts to lure the comic into discussing his life away from his mother’s television set. “Tell us what a person who has a life does,” Gottfried says. “You drink, you’re at an amusement park, and you puke. This is the fun life.”

The segment achieves its virtuosity near its midpoint, as Stern begins taking calls from listeners. Instinctively, the host and his guest turn on every dupe with the gall to phone them. In a surreal stretch reminiscent of a Marx Brothers routine, they place caller after caller on hold. (“You holding?” “Yep.” “Hold on!”) Finally, Stern lets a caller through. “Howard, you sound very, like, intimidated,” the man says. “You’re not yourself with Gilbert there.”

“Hey why don’t you eat me?” Stern snaps. “So okay—I’m intimidated, okay? You point it out. It isn’t an easy job.”

“No,” the caller stammers, “it’s a great job—”

“No, you can do better?” the host says. “‘You sound kind of intimidated?’ Hey jackass—”

“Why aren’t you at work, anyway?” Gottfried asks. “You’re out of work and you call this show to criticize someone with a job!”

As the call continues, Stern’s ire mounts and, at last, the stooge retreats. “Don’t try to apologize now!” Gottfried charges.

“What a dick,” Stern says.

Suddenly, Gottfried, whose normal speaking voice suggests a Looney Tunes character who has just stepped on a sharp object, erupts in full Daffy Duck sputter: “SHUT UP, SHUT UP, SHUT UP!” he cries. “I WANT OUT OF THE BUSINESS!”

Eventually, after he is repeatedly humiliated and before he is hung up on, the caller gets to what appears to have been his big question: “Who,” he queries, “was the executive producer of The Munsters?”

***

Gottfried’s Hollywood stock, in the conventional sense, probably peaked in the early ’90s, when he appeared in the Problem Child movies, voiced a parrot in Disney’s Aladdin, and hosted USA Up All Night, a B-movie program on basic cable. In 1987, he had headlined a sitcom pilot, Norman’s Corner, which aired as a Cinemax special before fading into the abyss. The show was co-written by Larry David just before he created Seinfeld. I have heard comedians—albeit mildly demented ones—swear by Norman’s Corner as the Seinfeld-that-might-have-been.

Now approaching 60, the comedian remains a prolific character actor and a reliably screeching voice in cartoons. His moments in the spotlight generally transpire because he has said something wildly inappropriate—a comedy mode that Gottfried has raised to an art form, if not raison d’être. In 2011, Gottfried famously got fired as the voice of the Aflac duck mascot after writing a series of corny Twitter jokes about the Japanese tsunami. (A sample: “I fucked a girl in Japan. She screamed, ‘I feel the earth move and I’m getting wet.’”) The loss of the long-running commercial gig clearly unnerved Gottfried, a notorious penny pincher who was apparently unaware that Aflac conducts the bulk of its business in Japan.

A decade earlier, however, his pathological yearning for vulgarity yielded what likely will prove his career apex. Appearing at a Friars Club Roast weeks after the World Trade Center attack, Gottfried took the podium bedecked in the kind of ill-fitting tuxedo a circus monkey might favor and cracked what Frank Rich, in the New York Times, described as the first public 9/11 joke: “I have a flight to California. I can’t get a direct flight—they said they have to stop at the Empire State Building first.” The joke was met by boos and an audience member’s cry of “too soon,” a phrase that quickly entered the lexicon, deployed when a comedian has made an appalling remark about a recent tragedy. (With alarming frequency, that comedian tends to be Gottfried.)

A few years ago, my younger brother, on the occasion of his wedding reception, raised his wine glass in a gesture of formality and gave the greatest toast known to man: “This wedding is so cheap,” he said, “you know the divorce will be expensive.” It was succinct in its dreadfulness; to my knowledge, nobody in the family has dared even mention it in the years since we witnessed it, mouths agape. The brilliance of my brother’s toast was that its second half was so improper—bringing up divorce at one’s wedding!—that it nullified the arguably more distasteful sentiment of the sentence’s first half. Up on the Friars dais, Gottfried employed similar logic. Booed for mocking 9/11, he turned to a joke that was infinitely more deplorable: A family act goes to audition for a talent agent and “the father starts fucking his wife,” Gottfried began. “The wife starts jerking off the son, the son starts going down on the sister, the sister starts fingering the dog’s asshole, then the son starts blowing his father…. Then the daughter starts licking out the father’s asshole. Then the father shits on the floor, the mother shits on the floor, the dog pisses and shits on the floor. They all jump down into the shit, piss, and cum and they start fucking and sucking each other. And then they take a bow. And the talent agent says…‘What do you call yourselves?’ And they go, ‘The Aristocrats!’”

Gottfried’s monologue, a particularly randy adaptation of a dirty old comedy bit, brought down the house. The performance helped inspire a film, The Aristocrats, in which a gaggle of A-list comedians including George Carlin, Don Rickles, and Jon Stewart discuss and present new tellings of the classic joke. (Only Sarah Silverman approaches the sick grace of Gottfried, but she relies on a revisionist angle.) In the movie, the veteran comic David Steinberg notes that the Aristocrats itself is “not a great joke,” but “hearing Gilbert Gottfried tell a joke like that—it’s a Picasso.” Indeed, there is a strange musicality to the comedian’s lewdness. The unreserved glee which he applies to a phrase like “the mother shits on the floor” is contagious. He curses not in anger but in joie de vivre. To hear Gottfried shriek “fuck” is to reacquaint oneself with the joy and purity of experiencing the word as a child.

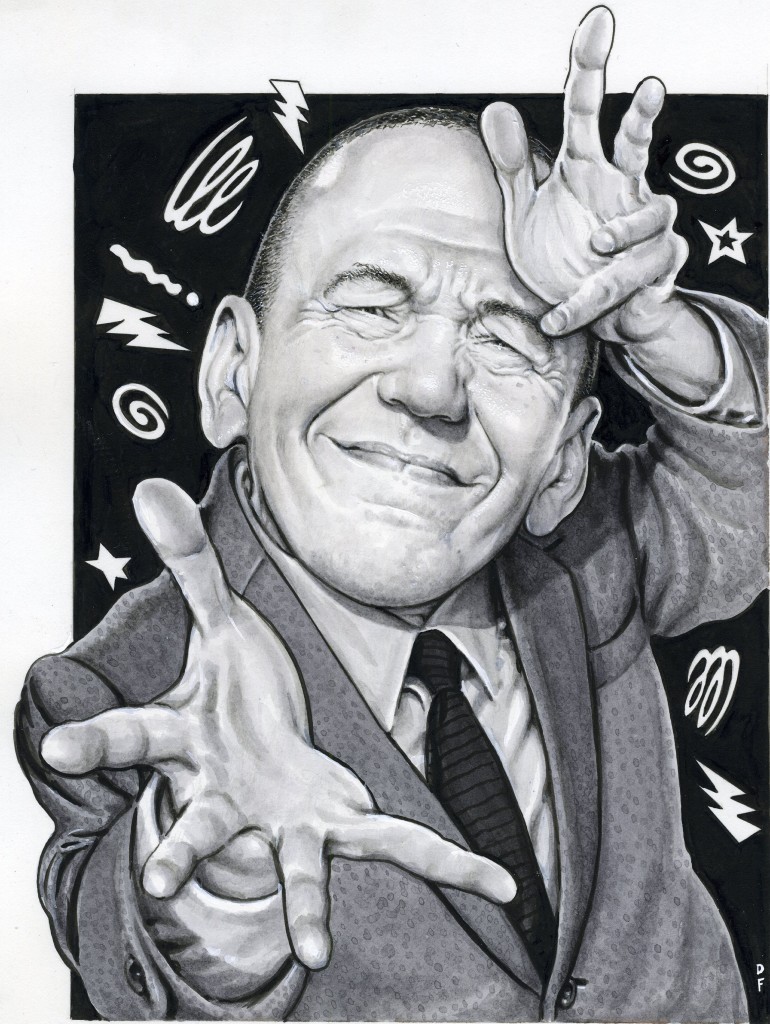

His standup act follows suit. Gottfried is a club comic in an old-fashioned mold. He avoids the trendy comedy spots of downtown and Brooklyn, in all likelihood because they tend not to pay their performers. To see him in New York, one must brave Carolines on Broadway, a Times Square club that somehow even smells like 1992. Onstage, Gottfried stands at a hunch, nerdily engulfed in a size-too-large shirt. He squints his eyes as if to ward off a fart, a visual trademark as recognizable as Pryor’s gait or Rodney’s tie fidgets, and speaks in a matchless holler that could unnerve the dead. He devotes a surprising amount of his stage time to disparaging midgets. Blacks and Asians he can almost accept as human beings, the comedian reasons, but he must draw a line at midgets. He says that he would like nothing more than to approach a midget and punch him in his midget face. At this, Gottfried draws back his arm and punches the air in a manner suggesting that he has neither punched somebody himself nor witnessed a person getting punched, even in a movie or on television. With a grace reflecting his decades onstage, the comic makes a strangely endearing child molestation joke: He envies those fathers who manage to lure their wards into incestuous relations, as he cannot even convince his daughter to hold his hand while crossing the street. Gottfried concludes his set with material from his Dirty Jokes DVD and wraps up the evening by repeatedly yelling, “a little boy with cum in his mouth!” The bulk of his set, however, is hardly blue. The comedian is a skilled impressionist, albeit mostly of long-deceased celebrities. Though not a prop comic, he ingeniously aids his impressions by placing strips of masking tape on his face—an elementary school cut-up gone pro. He does an extended bit about the sun and the moon that could kill in a third-grade classroom, as it did at Carolines.

Today’s younger comics, much like their indie-rock brethren, are mirrors of their audience: relatable figures in everyday clothes. They are slightly tweaked and often funny, but rarely dangerous. In contrast, nobody leaves a Gilbert Gottfried performance pleased that the comic thinks as they do. They leave believing that he is a deviant. He draws upon earlier eras of entertainment. He points to the ’80s, when he arose amidst walking cartoons like Pee-wee Herman and Andrew Dice Clay—both ultimately swallowed by their own creations—and loudmouths in colored leather. He is informed by the late ’70s, when he came of age surrounded by East Village punks—fellow Jewish geeks traumatized at home by Costanza parents and in the streets by a crumbling and forbidding city. Most of all, he evokes the fallen luminaries who ruled the Borscht Belt long before his time. It is their anarchic sensibility that Gottfried covets, reveres, and upholds. Of the fabled funny old men, he is the youngest.

***

Not long ago, I found myself without a day job for the first time in a dozen years. A free man! In my stretch of employment, as people do, I often had dreamt of being at such liberty. I would seize the city by its throat! I would leave no pavement unpounded, museum show missed, or alarm clock set. Naturally, once relieved of my job, I ended up spending most days eating peanut butter sandwiches by the computer, but there were some glimmers of the good life. I played tennis at three o’clock in the afternoon, took swims when inspiration sagged, went to Yankees games on whims, and assumed my spot at the B&H Dairy counter any time I desired, a king among men. I took to hanging out with another gadabout, Brian Abrams, a writer. Though in his early 30s, Brian had grown close to the legendary comedian Professor Irwin Corey, who was deep into his 90s. Brian and I began hanging out with the barmy comic at the old man’s Manhattan house.

Irwin Corey was born in Brooklyn in 1914—he celebrates his 100th birthday this summer—and spent much of his childhood in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. He is an avowed communist and a troublemaker; he has fire in his eyes, the glow of a champion rascal. Billing himself as “The World’s Foremost Authority,” beginning in the 1940s he would assume comedy stages garbed in the mock formal wear of a pretentious hobo, his hair popping with Einstein madness. “However,” his monologues would begin, before spiraling into head-spinning absurdism. In one clip, from The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, Corey presents a faux question-and-answer routine: “‘Professor, why do you wear tennis shoes?’” the comedian posits. “Well, ‘why’ has been plaguing man since time immemorial! Statesmen, philosophers, educators, teachers, scientists have been asking the ultimate why. And in these few moments allocated me, it would be ludicrous on my part, for the sake of brevity, to delve into the ultimate why. Do I wear sneakers? Yes!” In the mid-20th century, he appeared on television alongside Johnny Carson, Phil Silvers, and Steve Allen, and accepted a National Book Award on behalf of Thomas Pynchon. Sundry comedians bear the mark of Lenny Bruce; with Irwin Corey, the influence flowed the other way. After I began spending time with Corey, I learned that he had been a favorite comedian of my maternal grandfather, who died months before my birth.

Corey lives in the East 30s, in a carriage house that he purchased during New York’s rough patch. His home sits off the street in a private mew, the likes of which one normally encounters in less vertical cities. For years, his neighbor was Claudia Schiffer, whom Irwin described to me as a Nazi. “All Germans are Nazis,” he reasoned. When I first encountered Corey, his wife had recently died, after 70 years of marriage. Perhaps as a result of his grief, the Professor increasingly was spending his mornings collecting money from cars exiting the nearby Queens-Midtown Tunnel. He would mug and beg for the motorists, a feeble old man darting through traffic with his walker; come afternoon, he would return to his carriage house and count his winnings. Unbeknownst to the benefactors, every penny was being donated to a charity aiding sick children in Cuba.

Brian and I usually found the comedian in his dining room, carefully counting his morning’s take. On the wall hung memorabilia from his life and career: a photograph of Irwin with Fidel Castro; a message from Lenny Bruce; drawings by his grandson. Also on display was a framed letter of apology from Hugh Hefner, which may qualify as the single most Jewish item in New York City. Observant types, with their mezuzahs and ketubahs, are rendered mere goyim, trembling at the feet of the man with a framed letter of apology.

As might be construed from his act, the Professor is a longtime aficionado of marijuana. When he finished tallying the Cuba money, he would dig out his pipe and attempt to peer-pressure us into smoking with him. “I’m too old for that shit,” I would say, waiting for a laugh that never came. Once suitably stoned, the comedian would sound off on topics large and small: World War II, socialism, Rodney Dangerfield. One afternoon, the Professor asked Brian to cue up a favored VHS tape, in which a Jewish liberal debated a Christian conservative on PBS. When the Jew landed a rhetorical blow, the comedian would cheer, as if we were watching a ballgame. At one point, the conservative began stammering, tripped by his own logic. “Choke on a cock in your mouth!” Irwin jubilantly yelled at the screen.

***

I last visited Professor Corey’s house just after his 98th birthday. Weeks earlier, he had performed at the publication event for the Lowbrow Reader’s book anthology, at the Housing Works Bookstore in Soho. Although he had agreed to a five-minute appearance introducing the musician Adam Green, Corey stayed onstage for roughly half an hour, brazenly ignoring the bookstore’s pleas to step down. During his performance, he derided Franklin Delano Roosevelt as a “fucking cripple,” due to the president’s failure to save more Jews from the Holocaust; because my name rhymes with “gay,” he mocked me from the stage as a homosexual. He neglected to introduce Green. It was, in short, a sterling set—more than I ever would have hoped for—and I wanted to thank the comedian.

I arrived at his house to find it alive with company: Along with Irwin and Brian sat a puppeteer and his girlfriend, as well as Gilbert Gottfried’s wife and young daughter. Gilbert was on his way, his wife explained; because of the comedian’s frugality, he avoids taxis and public transportation, so he was coming on foot. Everybody laughed at Gilbert’s expense including me, despite the fact that I had walked there myself, as is my habit, for much the same reason. In time, the front door swung open to reveal our party’s final guest. The old man’s face lit up, as happy as I had ever seen him. “Gottfried!” the Professor exclaimed.

Offstage, comedians are often bores, and Gottfried himself has a reputation for debilitating shyness. The illustrator Drew Friedman once told me how in the ’80s, Gilbert would drop by his East Village apartment unannounced, requesting to watch Lon Chaney, Jr. movies. (“I don’t think he had a VCR,” Friedman said. “Too expensive.”) The comedian would watch the TV in silence as the illustrator worked, then leave. For a dozen years, I have passed Gottfried on the streets of the Manhattan neighborhood where we both live; he never fails to look more mortician than clown.

But to encounter Gottfried at Corey’s house was to witness the funniest man in town. Like the Professor, he is a scalawag who always emits the whiff of being up to no good. He has a herculean, liberally deployed laugh that seems a feat of athleticism, erupting through Pavarotti lungs to shatter glass and agitate pets all the way to New Jersey. You picture him marooned on a desert island, telling sex jokes to the fish.

At the Professor’s, lemonade was served and jokes told. (Irwin: “On his wedding night, a groom asks his bride, ‘Is this really your first time?’ The bride says, ‘Why does every man ask that?’”) Gottfried attempted to repair his broken eyeglass case with Corey’s denture adhesive, unsuccessfully. Corey was chagrined that the Gottfrieds had brought their five-year-old daughter, thus thwarting him from smoking marijuana, but the child ultimately seemed to win him over. Eventually, the party adjourned upstairs to view a nude oil portrait of Susan Sarandon that, for some reason, the old man possessed in his third-floor library. “Are you coming upstairs to see the Sarandon?” I asked Gilbert.

“Why would I walk up a flight of stairs if I don’t have to?” he said, as if we were embarking on a trek through the Arctic tundra.

When the party returned downstairs, Professor Corey was fast asleep in his chair and Gottfried was nowhere in sight. He emerged from the kitchen holding an enormous butcher knife and a bottle of ketchup, his face dramatically contorted, like a Messerschmidt sculpture. After carefully smearing ketchup on the knife, he posed behind the sleeping old man, brandishing his bloodied weapon and scowling murderously. It made for a handsome iPhone photograph and tickled Gilbert’s daughter to no end. But something tells me that if he were to find himself in the house alone with the Professor, Gottfried would have conducted his affairs no differently.

***

Gottfried maintains an active work calendar. In recent years, he has released a standup DVD, Dirty Jokes, and published a memoir, Rubber Balls and Liquor. He tours frequently and seemingly agrees to any character role that comes his way, be it in Hannah Montana or Law & Order. In 2013, he made a pitch-perfect appearance on Celebrity Wife Swap in which he shared his apartment with the dolled-up third wife of Alan Thicke. Gottfried mocked his guest at every turn, playing up his cheapness to a grotesque degree. “What are you, the Queen of England?” he asked when she balked at eating a free dinner inside the Friars Club’s kitchen, with chefs busily working around her. Every moment Gottfried is onscreen, the episode resembles a Sacha Baron Cohen bit more than it does a network reality show.

Gottfried’s best work, however, generally comes on The Howard Stern Show. Since the initial 1987 appearance, he has returned to the program countless times. Of the show’s recurring guests, only Chris Rock and Joan Rivers are in a class with Gottfried. As a Stern guest, he represents the rare trifecta: celebrity, funnyman, and nut. His barometer of appropriateness reliably skews dirtier than that of Stern, who, next to Gottfried, can appear prudish and reserved. For all his reputation as a Portnoy-esque ogre, Stern is a portrait of calculation and control, a broadcaster capable of thinking three minutes ahead at any give time. Gottfried, by contrast, is a wild man, fearless in his pursuit of a laugh. He insults those around him, self-deprecates, and unleashes ethnic slurs with abandon. The constant destination is the laugh; how he arrives there matters little. Like the onscreen relationship between Bill Murray and David Letterman, the guest presents a consummate vision of the host’s sensibility—an untamed dream of what Stern might be himself, were he not wed to the responsibilities of a show.

Sometimes, Gottfried surfaces on the program in the guise—or semi-guise—of a character. There is Dracula Gottfried, who, in the days following Nicole Brown Simpson’s murder, took to the streets dressed as a vampire to ask black passersby whether they believed O.J. Simpson to be innocent. There is Rabbi Gottfried, who prattles on in faux-Hebrew song while dispensing Jewish wisdom. (“I spit in the Coca-Cola and it makes it kosher.”) He impersonates fellow comedians: Jackie Mason, the Dice Man, and, especially, Jerry Seinfeld, who had yet to achieve stardom when Gottfried began ridiculing him. Most famously, Gottfried imitates the geriatric Groucho Marx, gently blathering about the old days on The Dick Cavett Show. (“Back in my day, if a person wasn’t married, they would refer to him as a ‘bachelor.’ This would be a man who did not have a wife. So they would say, ‘That person is a bachelor.’ Whereas if they had a wife, then they would say he’s a ‘married man.’”) The impersonation is at once ruthless and affectionate, as if Gottfried is skewering his own late grandfather.

The most anarchic character, of course, is Gilbert himself. He is eager to act the pest and push a joke several steps beyond its natural lifespan. When Abe Hirschfeld, an elderly parking lot magnate who had been jailed for calling a hit on his business partner, phones into the show, Gottfried asks him to repeat a dopey joke again and again. The effect goes from being funny to infuriating to hilarious to bizarre—part prank call, part Dada madness. Gottfried drools saliva into a box of cupcakes reserved for the radio show’s staff, apparently to the sole amusement of himself. He recalls opening a 1980s concert for Belinda Carlisle: Encountering an audience of young girls and their parents, and instructed by the promoters to work clean, Gottfried opted to perform a set of the filthiest “vagina jokes” he could imagine.

My favorite Gottfried appearance occurred in 1997, on a morning that he was not even scheduled as a guest. A thickly accented German-Jewish woman calls into the show from Los Angeles, claiming a beef with Gilbert. The German explains that she works as a babysitter for the filmmaker Amy Heckerling, who directed Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Clueless as well as Look Who’s Talking Too, which featured Gottfried in a supporting role. During a recent trip to Los Angeles, the comedian had been invited to Heckerling’s home for dinner; when his stinginess precluded a cab ride, the director dispatched the babysitter as a makeshift chauffer. During the ride, for reasons unknown, the German volunteered that her parents were Holocaust survivors. Does it go without saying that Gilbert began cracking Holocaust jokes? “My father weighed 80 pounds when he got out of the camps,” the caller informs Stern. “Gilbert said, ‘How can I go on a diet and lose that much weight? What did your father do?’ Things like that. Oh! It was so horrible! You have no idea!”

Stern gets Gottfried on the phone. The comedian appears to have been woken by the call, but, like a Navy SEAL who rises at any hour prepared to do battle, he instantly begins accosting the woman with Holocaust jokes. She is not pleased. “I made calls to [Gottfried’s] house,” the German reports, “and told him that I wish that Hitler’s dogs would have bitten off his penis.”

“Oh, wait,” Gottfried interjects. “The Germans are knocking at your door.”

“Gilbert, you’re gonna rot in hell with Hitler,” the caller says. “Stop making dirty jokes to 10-year-old girls.”

“Oh, Gilbert,” Quivers sighs.

“He made a dirty joke to a 10-year-old-girl?” asks Stern. He seems equal parts shocked and amused.

Naturally, Gottfried is unflappable. “I would like your job so I can wash her daughter every day,” he tells the nanny. “Can she sit on my lap while you tell her about the Holocaust?” And at last, without so much as getting out of bed, the comedian has seamlessly wed a child molester joke to a Holocaust joke. Behold…the holy grail of Gilbert Gottfried!

The entire exchange, as Stern might say, makes for great radio. But the durable image is of what happened off air, in the German woman’s car, where we encounter the private Gottfried and find him just as bawdy, irreverent, wicked, and hysterical as his public counterpart. The comedian walks a grueling and lonely path. In disregard of basic propriety, to say nothing of his own social life and career, he falls on his sword for the sake of a laugh. He holds back little, fearing nothing so pedestrian as slain feelings.

In adolescence, screwing around like an asshole comes naturally; even the most uptight and repressed teen has his moments. For adults, attaining such moron’s Zen takes a true warrior: Howard Stern, Professor Irwin Corey, Gilbert Gottfried. For a New York minute, liberated from the tedium of the working world, I slipped into the Professor’s rarified orbit. Unsurprisingly, it did not hold. Not long after encountering Gottfried and Corey, I grew fairly ill and began inching toward recovery; after 15 years of dilly-dallying, my wife and I had a kid. I never returned to the Professor’s house. But I never belonged to that world in the first place. Killing an afternoon with those nuts, I felt like a minor league call-up who suddenly finds himself batting against Rivera.

Of course, the thrill of listening to The Howard Stern Show, of witnessing Professor Irwin Corey perform and panhandle, of spying Gilbert Gottfried on or off stage, comes from observing masters of the goof-off, while hoping a dollop of their temerity rubs off. At any point in history, have grown men wasted time with the panache of such Americans? It is no easy task. These are men of chutzpah, New York City punks.

—Lowbrow Reader #9, 2014