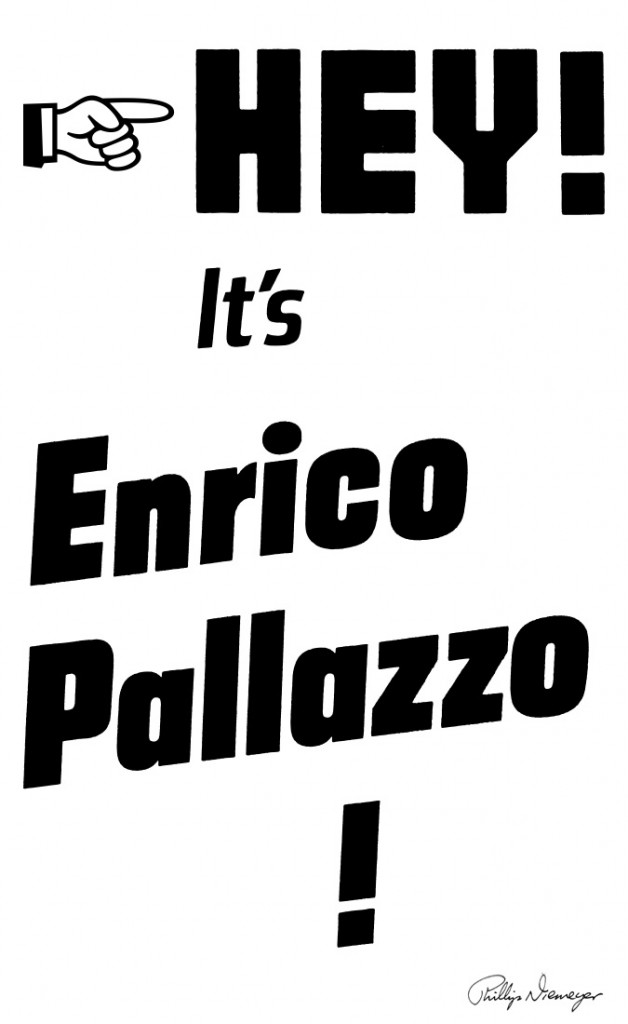

Hey! It’s Enrico Pallazzo!

[Article and illustrations from Lowbrow Reader #11, 2020]

It’s a blue-skied afternoon in 1980s California, and the Angels, with their mustachioed southpaw Dave Spiwack on the mound, are hosting the Seattle Mariners. Security is on high alert: Queen Elizabeth II is attending the game, and the Los Angeles Police Squad has uncovered a plot against her life, improbably involving one of the ballplayers. Clearly, only one man can thwart the assassination: Frank Drebin, a rogue detective who, following a number of idiotic infractions, was recently removed from the force.

The scenario, of course, comes from The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad!, the landmark 1988 slapstick film starring Leslie Nielsen as the bumbling Lieutenant Drebin. Any distinguished cinephile is familiar with the anarchy that follows: Drebin, desperate to get on the field to unmask the potential assassin, gags and hogties the opera star who had been slated to perform the National Anthem—a certain Enrico Pallazzo. Introduced as Pallazzo and garbed in the singer’s tuxedo, Drebin mangles “The Star-Spangled Banner” with unsurpassed ineptitude. The detective then switches covers to impersonate the home plate umpire, fumbling his way through officiating the game. By the seventh-inning stretch, it has devolved into madness and the would-be killer appears: a hypnotized Reggie Jackson, Mr. October himself. Drebin handily foils the plot when his tranquilizer dart strikes an obese woman in the upper deck, who tumbles onto Jackson.

Having saved the queen, Drebin removes his umpire mask and turns to the crowd with a vacant grin. And here, as The Naked Gun barrels to its conclusion—with countless rapid-fire jokes in its wake—the movie unleashes its funniest and most celebrated punchline. In the stands, a spectator recognizes the heroic umpire from his previous cover. The pudgy fan wears greased-back hair, a gaudy ring, and a period tracksuit. His eyes bug out as he excitedly points at the lieutenant and delivers his sole line of the film: “Hey! It’s Enrico Pallazzo!”

The Naked Gun was directed by David Zucker from a script by Zucker and his brother Jerry, plus Jim Abrahams and Pat Proft. Coupled with the 1980 disaster parody Airplane!—the handiwork of the Zuckers and Abrahams—the movie defined the anything-goes cornball aesthetic that flourished throughout the ’80s. The baseball set piece is the genre’s apotheosis, capped by that one stray bit of dialogue: “Hey! It’s Enrico Pallazzo!”

The line is the “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn” of slapstick. In the years since the movie’s release, there has been an Enrico Pallazzo racing thoroughbred, a requisite Family Guy shout-out, and a bevy of novelty merchandise. Enrico Caruso, the Italian tenor who likely served as the character’s namesake, played a dominant role in early recorded music and became the first artist with a million-selling hit (“Vesti la giubba”). For many Americans, Caruso’s fame was long ago eclipsed by Pallazzo. And why not? Hey, it’s Enrico Pallazzo.

***

Where did this line come from? Why did it triumph? Why has it endured? It’s an odd joke: a belated punchline to an ostensibly concluded bit. Because most jokes in The Naked Gun and its farcical ilk come and go with lightening speed, the very existence of such a callback is a surprise. Much of its uncanniness also lies in the tracksuited figure speaking the line: the journeyman comic actor Mark Holton. The actor was hardly famous enough to rank among the film’s cameos. Yet he also seemed too familiar a screen presence to fill a role simply titled, in the film’s penultimate acting credit, “It’s Enrico Pallazzo!”

At the time of The Naked Gun’s release, Holton was just three years removed from a busy summer on screen: In 1985, he had co-starred in Teen Wolf (as Chubby) and Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, in which he played Pee-wee Herman’s loathsome nemesis, Francis Buxton. But at the time, Holton didn’t think much of his two-second scene. He has little memory of how he landed the role. It was just another gig—a one-day shoot when he was an unusually boyish 35. “I don’t think I went to the screening,” Holton told me, speaking from his home in Oklahoma. But soon after the movie’s release, “I was walking down the street in Hollywood. A guy pulled up in a big black pickup. He rolled by very slowly on the curb. He lowered his window, pointed at me, and said: ‘Hey! It’s Enrico Pallazzo!’ And then he just drove away. I was dumbfounded. I thought, Wow—I guess I better go to the theater tonight.”

It was not as if Holton had been unaware of the significance of participating in a production headed up by ZAZ—the unofficial acronym for the surrealist parody trio of Zucker, Abrahams and Zucker. The actor said he was “crushed” when Police Squad!, their short-lived TV series that would later birth The Naked Gun, was canceled after a measly six episodes. It just never occurred to the actor that such a brief snippet of screen time could evolve into one of the more memorable roles of his career. “I had no idea that people would remember that specific line,” he said.

Pat Proft, one of The Naked Gun’s four screenwriters, worked on Welcome Back, Kotter, The Carol Burnett Show, and the infamous Star Wars Holiday Special before landing a job on the Police Squad! series, which yielded him more than two decades of ZAZ-related work. Holton “was perfect for it,” Proft told me, calling from his home in Minnesota. “It’s so stupid, but in that second he performed it so great. He really was thrilled that the man who sang the National Anthem actually saved the queen!”

After speaking with Proft and Holton, I phoned David Zucker in Los Angeles. The director seemed baffled at my attempt to put so much focus on the Pallazzo bit. “People have kind of glommed onto that one,” he said. “And I’m not entirely sure why. It was a very easy joke to make. Real low-hanging fruit. I can’t remember who thought of it or when we came up with it. I’m pretty sure it was in the writers’ room and not on the set.” None of the jokes in the film, Proft assured, were whipped up “on the fly.” They were all crafted—“crafted!” he repeated with sarcastic emphasis—in the writers’ room.

“I have a lot of stuff in the baseball [sequence],” Proft added. He referenced jokes from the preposterous baseball bloopers reel that plays on the stadium’s jumbotron. “The tiger that jumps on the guy and the guy who goes back and his head flies off—all that stuff was pretty much me. And then, if Drebin saved the queen and someone recognizes him as Enrico Pallazzo was such a simple thing to do. It was a wonderful button to it all. But I didn’t know it’d be that great. I remember at the premiere, people just laughed so hard at that.”

To Holton, it was mostly a paycheck: under $400 if his memory serves, less 10 percent to his agent. (Fortunately, he did not employ a manager, saving him about $100.) By that point in his career, the actor knew what the drill for the union-scale day rate would entail: Drive to Dodger Stadium (which was, strangely, standing in for the less fabled Angel Stadium); report to hair and makeup; pop into wardrobe (anyone with a speaking part was assigned an outfit); and, in a matter of hours, soldier through a handful of takes amid an ocean of extras. “It wasn’t just one take,” Holton recalled. “But I don’t think we had to spend a whole lot of time on it.”

Then, presumably, Holton would turn to the pursuit of the next bit part. It was a strange path for an actor who, three years prior, had co-starred in a blockbuster comedy, even stealing scenes from the titular lead. But it was a path he chose. “The thing that I didn’t like about the notoriety I got from Pee-wee’s Big Adventure,” Holton said, “was that I had audition after audition of people trying to get me to play the same character. I was shocked—my god, here’s another one.”

Casting directors “wanted me to be Francis Buxton,” he continued. “There was a very long stream of auditions where it almost seemed like they didn’t understand that I was an actor playing Francis Buxton. I finally told my agent, ‘I’m not gonna play Francis Buxton again. Even if it costs me a lot of money, I don’t care.’ I was fortunate enough to land commercials during that period of my life, which helped a lot. It kept me from having to become a waiter or wash dishes or whatever.”

***

Paramount Pictures predetermined The Naked Gun as something of a non-priority for its 1988 winter slate, a decision based on a proven strategy for a previously shepherded ZAZ project. Nearly a decade earlier, Frank Mancuso, then head of distribution for the studio, deliberately scheduled the opening for Airplane! in the dead of summer: July 2, 1980. (ZAZ’s debut, Kentucky Fried Movie, was independently released in 1977.) Opening Airplane! on the holiday weekend, per Mancuso’s thought process, would allow for all the marquee summer titles to cycle through the season. Some would succeed. Others would bomb. Nevertheless, no need to go up against the anticipated heavyweights. Rather, let them fight among themselves and wait for a calmer period to roll the dice on a goofball $3.5 million production about a PTSD-addled war veteran—with a very unusual drinking problem—who is forced to land a passenger flight after its captain and crew fall ill from food poisoning. They all had the fish.

Airplane! became one of the highest grossing comedies in history ($38 million in its first year) and Mancuso would soon find himself bearing the titles of chairman and CEO. It was a no-brainer for the studio head to run the same play when it came time for The Naked Gun, budgeted at $14.5 million and set to open December 2, 1988—after Paramount’s costly Bill Murray vehicle Scrooged hit theaters, but just before the industry blitz of Oscar bait (which included Rain Main and Mike Nichols’s Working Girl).

“We never went in as the frontrunner—we were kind of the tugboat in the middle of the aircraft carriers that had to squeeze through,” David Zucker said. “So it may have been, again, Mancuso’s marketing genius that was a big part of Naked Gun’s success.”

No controversies materialized during production, the film’s editor, Michael Jablow, noted. “O.J. Simpson was always nice,” he remarked of the football star who, six years ahead of his Bronco ignominy, played Lieutenant Drebin’s largely incapacitated partner. “He never, ever put his hands on me. Never came at me with a knife—nothing like that.” Other challenges presented themselves prior to the release. A title proved especially vexing. According to Zucker, Mancuso expressed concern over how the working title, Police Squad!, could create “a conflict of potential confusion with Police Academy.” So the studio head commissioned the marketing department to generate a list of a few dozen alternatives. Wagons circled fairly quickly around The Naked Gun. (Its competition included the even more suggestive Bang Bang Bang.) Still, Jablow described a test screening in Sherman Oaks, populated by a bunch of “14-year-old Siskels and Eberts.” For whatever reason, the teenagers determined that the new name “sucked.”

The internal debate over the title lasted three months, as Jablow remembers it. The delay postponed production for the originally intended opening credits sequence: A James Bond homage with “naked fat ladies swimming underwater in silhouette,” accompanied by a theme song recorded by Engelbert Humperdinck. Time ran out for the shoot, resulting in a spartan opening credits montage featuring a police siren, used as a last-minute fallback. “In the end,” Jablow recalled, “Frank Mancuso said, ‘You know, I had a movie called Raiders of the Lost Ark that everybody thought was about Noah. Just call it The Naked Gun.’”

“I mean, you have ‘naked’ in the title,” Zucker noted. “It was great. So much of this was Mancuso. When we pitched the movie, he just said ‘yes.’ He knew immediately. Instead of saying, ‘What? You want to make a movie out of a failed television series? C’mon!’ But there was none of that. He was as good in his own right as some of the great people at the studio who came before us, like Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg.”

Mancuso and the Zucker team prevailed. In its first three weeks, The Naked Gun racked up $26.2 million and consistently outperformed Scrooged. The New York Times characterized the film as “the box-office phenomenon of the pre-Christmas season” and reported the development of a sequel as “inevitable.”

***

Of course, much credit for The Naked Gun’s triumph belongs to the script, its pages overrun with gags. Proft acknowledged having a near-formulaic system in which the workhorse would ensure three jokes per page (meaning per minute) throughout the 85-minute runtime. If some jokes didn’t work, fine; toss ’em. Imagining the crew working on one laugh line after another, it becomes apparent why no one had any expectations for “Hey! It’s Enrico Pallazzo!” to achieve any special renown.

“My favorite Naked Gun gags were the ones where we didn’t have to try too hard,” Zucker said. “Where nobody’s trying to be Jerry Lewis or Jim Carrey. Those guys were very funny in their own right, but [my favorite lines came across] just natural. Like ‘nice beaver.’ Or [when Drebin drives past] the two nuclear domes and says, ‘Everywhere I go, something reminds me of her.’ Nobody made a face. Nobody jumped up and down or tried to be funny. It was just actors reading lines.”

According to Proft, “the reason why the movies did so well internationally is because of the physical humor involved. But it’s not just slapdash, hey, let’s fall down humor. Slapstick has to have reasons—it can’t just happen. There has to be a reason that something has occurred.”

In the confines of broad slapstick, subtle details can work wonders. But how much was intentional? I asked Zucker whether dressing Holton in a tri-colored tracksuit was deliberate, a way of lightly mocking ’80s fashion during the ’80s. “I think we paid more attention to [wardrobe for] the slackers who were in the queen’s seats,” the director said. Sending up ’80s fashion “would be a brilliant joke—but we were just concentrating on making him look like a guy at a game. I don’t think it went any deeper than that.”

The tracksuit would have been the domain of Mary Vogt, a costume designer then in the infancy of a career that would go on to include Men in Black, Crazy Rich Asians, and countless other productions. “We just thought that’s what he would wear to the ballgame,” she explained to me, while recognizing that, in retrospect, the garment is a conspicuous artifact from another era. “Tracksuits were very big at that time. When you look at the movie now, everything looks a little hyper-realistic. But the ’80s were like that. It’s very hard not to let the time period that you’re in influence the costumes or look of the picture. A good parlor game would be to show movies and ask what year they were filmed. Okay, this is a 1940s movie. What decade did they actually do it in? Did they do it in the ’70s? Or did they do it in the ’90s? Because they would look different. It’s easier to do, like, the 15th Century, because nobody knows what that really looks like.”

In the 21st Century, Holton does not wear tracksuits, nor does he seem resentful for rejecting those potentially lucrative, Francis Buxton cookie-cutter offers. He continued working consistently enough, even after relocating to the High Desert where home ownership was possible for him but by all accounts too far to commute for casting calls. He would crash on friends’ couches in the San Fernando Valley for the occasional audition, but would eventually call it quits, sell his home for quadruple its original value, and abandon California altogether.

Holton’s filmography slowed around 2008. In the past decade, he has maintained a low profile at his home outside of Tulsa, near the part of Oklahoma where he grew up. The actor and his wife have been able to put both their sons through private school, and his 1987 Volvo 740 Turbo still sits in the driveway. He’s no social media showboat. Call his cell to hear how he has remained happy and humble after all these years.

An anecdote Holton shared from his ’80s heyday indicates that he was no different back then. “The summer that Pee-wee’s Big Adventure and Teen Wolf came out—they were the number-two and -three comedies right behind Back to the Future—I was helping the manager for the property where I had a rent house. He’d come get me and say, ‘Hey, man, I need you a couple of hours. I’ll pay you.’ So we went back to a duplex. He had a plumbing problem where sewage was coming up in this flower bed. I had to dig it out so he could get a snake in there, and these people were flushing the toilet even though he’d asked them not to.

“This lady came out and lit a cigarette on the porch. She had her night clothes on and her hair up in curlers. I’m down on my hands and knees with mud all over me in a crappy old shirt. She pointed at me and goes, ‘You look just like a guy in a movie that I took my kids to see this weekend.’ And of course, the guy I was working with points and goes, ‘Yeah, that’s him!’ Sometimes, life throws things at you, makes sure that you stay grounded in reality.”

With regard to the ZAZ collective, its effective run came to a close shortly after “Hey! It’s Enrico Pallazzo!” boomed across theaters. “We had an ending, which was great,” reminisced Proft, speaking again of the baseball sequence—or perhaps something more existential. “It was a place that we could tack a lot of jokes onto, and there were thousands of people watching and all that kind of stuff. It was a great place to end it. Jim [Abrahams] broke off pretty much after that.”

By the summer of 1988, Abrahams had already begun to direct films independent of ZAZ—his rambunctious Shakespeare adaptation Big Business reteamed him with Bette Midler, who had starred in ZAZ’s 1986 kidnapper farce Ruthless People. But his departure from the group is more often marked by his helming of the Hot Shots franchise. Proft, ever the ZAZ loyalist, assisted Abrahams writing Hot Shots jokes. Jerry Zucker directed—somewhat incongruously—the 1990 romantic sleeper hit Ghost. As for David Zucker, he continued to lord over the Naked Gun franchise, which years later was reason enough for Bob Weinstein’s Dimension Films to tap him for several Scary Movie installments; naturally, Proft was in the writers’ room.

I first interviewed David Zucker in 2008, for Heeb magazine. At the time, he characterized ZAZ’s rupture as amicable, one in which they “decided to loosely be involved with one another” after nearly 20 years of sharing credits. (Zucker also noted that it became impractical to continue splitting a salary three ways on projects like Ruthless People, where there was no back-end deal.) A dozen years later, the team remains apart. “It was kind of like the Beatles breaking up,” Proft told me. “Everybody wanted to go off and do their own stuff. Naked Gun felt a little like Abbey Road.”

Yet Proft is being modest. Abbey Road gave the world “Here Comes the Sun” and “Come Together,” the knockout concluding suite and “In the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.” But nowhere, backward or forward, did it yield a chubby man in a tracksuit yelling “Hey! It’s Enrico Pallazzo!”

—Lowbrow Reader #11, 2020