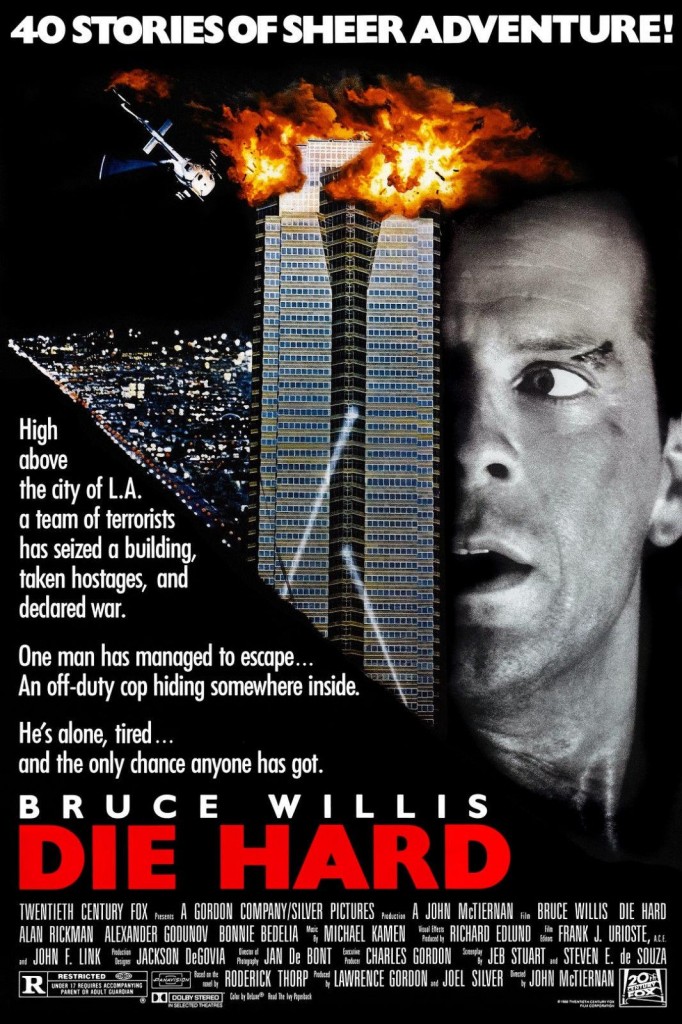

Is Die Hard a Christmas Film?

As the temperature drops and more trees don sparkling lights, an annual holiday season debate is renewed: Is Die Hard a Christmas movie?

And yet there is another query that is truly the one worth pondering: Is Die Hard a Christmas film, not a mere movie?

In the 1988 picture’s first scene, cinematographer Jan de Bont keenly focuses upon an airplane armrest tensely gripped by New York City police officer, John McClane. It’s a foreshadowing: The upcoming thrills will be aspirationally Hitchcockian, as unnerving as early-to-mid Friedkin or spring of 1931 Lang.

And also there will be Christmas carols.

In the blink of an eye, we see McClane procure a giant teddy bear from the overhead compartment—presumably for one of his progeny but almost assuredly a nod to the 1966 Clint Walker feature, The Night of the Grizzly—as Bing Crosby–worthy sleigh bells echo through the soundtrack.

Two minutes in, we’ve already got sleigh bells.

Upon his arrival in Los Angeles, McClane is greeted by a limousine driver, Argyle—the Sancho to his Don Quixote, the Virgil to his Dante, the Spielvogel to his Portnoy. Argyle’s musical selection—from seminal hip-hop group Run-D.M.C.—is in direct lineage with the usage of contemporary music from 1970s New Hollywood auteurs like Scorsese, Nichols and Hopper.

It is also a Christmas song.

McClane’s destination is his estranged wife’s office tower, which bears features that—try as they might—cannot escape comparison to the 1927 German expressionist feat, Metropolis. Holly McClane is a high-powered businesswoman, who embraces her maiden name and has a steel-like demeanor that recalls a long line of film heroines who find a true genesis in 1928’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

Her company is also throwing a totally kickass holiday party.

The crux of Die Hard rests upon the shoulders of McClane, himself, who is portrayed by Bruce Willis. Director John McTiernan acts as a nouvelle vague Godard, harnessing his own vision yet trusting his star. McClane’s one-liners are akin to Michel Poiccard’s mutterings in A Bout de Souffle, yet are fashioned with a self-aware wit reminiscent of Woody Allen in the mid-to-late 1970s.

Willis’s character—a reluctant hero like Harrison Ford as Han Solo, Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones or Harrison Ford as Rick Deckard—is imbued with a spontaneity, a questioning of reality, a modern look at the world.

At one point, in the true spirit of internal pondering and a new year dawning, he resounds, “Why don’t you take this under consideration, motherfucker?”

Like the Odessa Steps scene in Battleship Potemkin, the plot takes a sensational turn upon the arrival of an international terrorist group led by Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman). The collective—in a classic heist twist (that owes a large debt to 1973’s The Sting)—acts as revolutionaries before outing themselves as sophisticated mercenaries.

And also they’re Germans. And Germans love Christmas.

Die Hard teems with the holiday season, from the constant reappearance of the leitmotif of “Ode to Joy,” to lit trees behind police dispatchers, to “Let It Snow” playing over the speakers at a convenience store. And, again, as the credits roll.

As the camera moves throughout the floors of the expansive skyscraper set, the mise-en-scène is so cheerful that it can only be temporarily interrupted by an unarmed, innocent man being shot point-blank in the face.

Adopted from the 1979 novel, Nothing Lasts Forever, the violence of Die Hard is visceral, calling upon battles once envisioned by Kurosawa, Peckinpah or de Palma. And then there’s the part where McClane breaks a terrorist’s neck while they’re wrestling down a set of stairs, dresses him up in a Santa hat and writes “Now I have a machine gun, ho-ho-ho” in blood on his shirt. It’s a scene grisly enough to quench Tarantino’s thirstiest bloodlust.

‘Tis the season!

Hostages, including his wife, have been taken and McClane must free them. At one point, he finds himself maneuvering through an air shaft as the camera’s realistic work foreshadows the Dogme 95 movement and the briefcase scene in 2007’s Coen Brothers classic, No Country for Old Men. Gruber, himself, exhibits his cinephilia as he and McClane discuss archetypal Western heroes before the venerable police officer declares his devotion to Roy Rogers.

Is it a coincidence that Rogers recorded an album, Christmas Is Always, in 1967? A thought.

In perhaps its most festive scene, one of the terrorists mockingly recites the opening stanzas of “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” as the group viciously wounds dozens of police officers and, eventually, destroys their vehicle with a rocket launcher.

Straight to the naughty list!

Die Hard, with deference to, reverence for and reference of 20th century American Western film, surfaces many uncertainties surrounding bloodshed, manhood, anti-government sentiments, Reagan-era greed and fear of immigration.

But, Christmas? No. Christmas. Good.

In the end, McClane emerges a Nietzschean Übermensch, the only earthly being who can see to Gruber’s demise—a fall all the way down the tower, the King Kong of Los Angeles.

As the hostages run free, John McClane, the bloodied, barefooted hero, might be considered Christlike, the chosen one who freed the masses from what binds them.

And, hey, what’s more Christmassy than Jesus?