Ladies and Gentlemen, Put Your Hands Together for the Most Vulgar, Vicious Comic Ever to Walk the Face of the Earth, Andrew Dice Clay

[Article and illustrations from Lowbrow Reader #11, 2020]

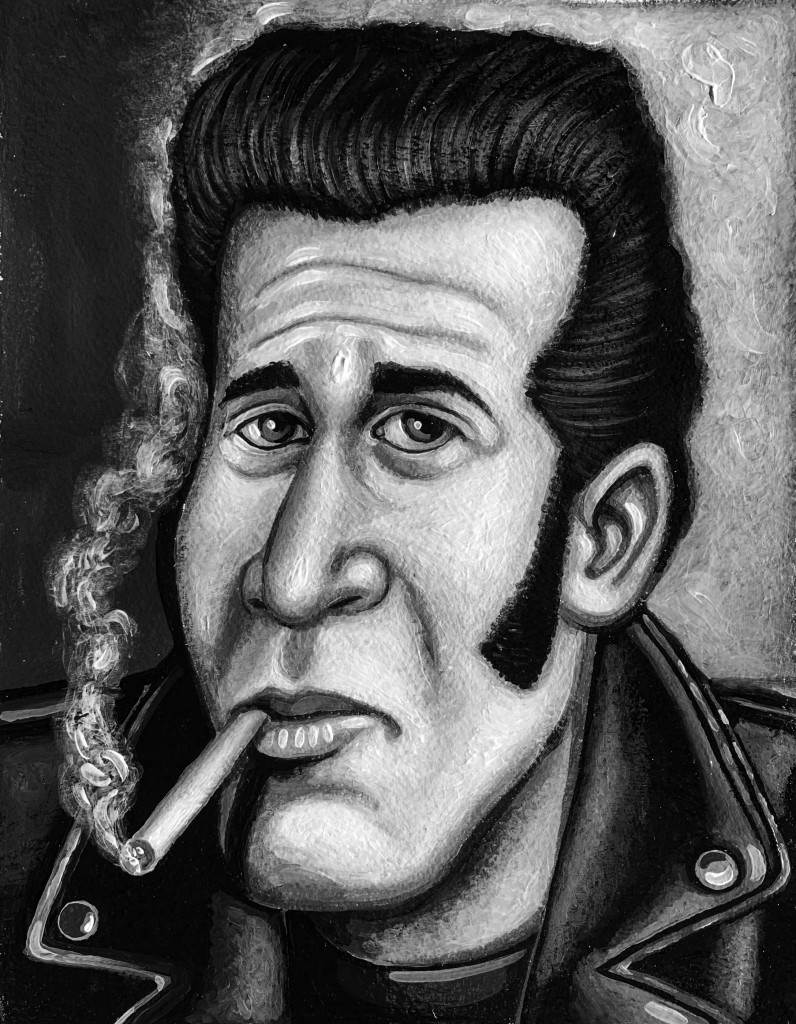

In the waning days of the 1980s, a boorish goon in sleazy leather took the stage of an Upper East Side club to record an avant-garde comedy album. A cartoon of a man, he wore broad Fonzarelli sideburns and an imposing pompadour, jet-black and groomed to the standards of the French noblesse. He brandished a cigarette in the ostentatious manner of an old-time hoodlum, between thumb and index finger. His words were sordid, as if lifted from graffiti found on a prison toilet stall, then coarsened for a less squeamish crowd. He was, per self-description, “The most vulgar, vicious comic ever to walk the face of the earth.” No joke.

At 32, Andrew Dice Clay—our beloved goon—was a newly-minted cultural phenomenon, on his way to selling out Madison Square Garden two nights running, a first for a comedian. The 1990 Garden performances—which the New York Times compared, unfavorably, to Nazi rallies—would feature Tri-State mobs cheering Dice as he recited the randy nursery rhymes that had brought him fame. “Jack and Jill went up the hill, both with a buck and a quarter,” he pronounced, the arena’s swarm giddily shouting along. “Jill came down with $2.50. Owww! That fucking whore!” To watch the Garden show, immortalized in the concert film Dice Rules, is to crave a shower and a signed first edition of The Feminine Mystique.

The Upper East Side appearance was different. Clay had descended upon Dangerfield’s comedy club at the behest of his producer, Rick Rubin. It was Christmastime, and the 200-or-so patrons had found themselves at a Dice show unwittingly. That he was unbilled was not uncommon for Manhattan comedy clubs, with their tradition of starry drop-in performances. But the standup had chosen this unwelcome and at times hostile setting to record a live album: The Day the Laughter Died, uncompromisingly presented over 102 exhausting minutes and two CDs, with no conspicuous edits.

On The Day the Laughter Died, the tough-talking Dice persona, honed over a decade of performance, seems every bit as repugnant as in the Garden special. The misogyny, xenophobia, homophobia, and all-around vileness inherent to the act are unabated. Yet the perspective has shifted. Rather than preening before his partisans, Dice confronts a skeptical and seemingly disgusted audience. He renounces his prepared material, relying almost entirely on improvisation. His delivery is soft and flat, steered by his exaggerated accent of a bygone blue-collar Brooklyn. Some of the biggest laughs come from routines that emerge from stream-of-consciousness, and do not necessarily make any sense. (“Call you in an hour—back! Get it? Hour back, get it? Hour back! I’ll call you in an hour. I’ll get back to ya! Hour back—get it?!”) Most startling, there are extended patches of silence—including the album’s opening minute, which is consumed by the comedian wordlessly lighting a cigarette. Ignoring the barroom lexicon, the recording sounds like something you might hear in a Janet Cardiff installation. As with all of the best Andrew Dice Clay work, the album feels at once dangerous and bewildering.

The Day the Laughter Died was released on Rubin’s American Records imprint in early 1990, halcyon days for the Diceman. That May, he hosted Saturday Night Live, prompting cast member Nora Dunn to boycott the episode in a torrent of publicity. (Also bowing out was the week’s originally scheduled musical guest Sinéad O’Connor, thus depriving audiences of the most ill-fated blind date in time immemorial.) His appearance at the MTV Video Music Awards won him a lifetime ban from the network—which, for a blue comedian, was roughly equivalent to winning a Nobel Prize. In middle-school cafeterias nationwide, prepubescent boys declaimed Dice’s moronic Mother Goose rhymes. The Adventures of Ford Fairlane, a film starring the comedian as the titular “rock & roll detective,” opened wide in theaters that summer, with Wayne Newton, Priscilla Presley, and Gilbert Gottfried in supporting roles. Dice was everywhere.

And yet, like much culture of the late ’80s and early ’90s, the comedian’s reign was short-lived. By 1993, his shtick already seemed a piece of some distant past, hosed down the gutter along with such noxious fare as hair metal, MC Hammer, and Dan Quayle. It was the year of Bill Clinton and In Utero, Liz Phair and Seinfeld. And it was this year that the comedian returned with Rubin to Dangerfield’s comedy club to record The Day the Laughter Died, Part II, the album’s abrasive, little-remembered sequel. Improbably enough, it was here, in the record’s final minutes, that the comedian realized his disturbed masterpiece: “The Argument,” an effective denouement to the album, if not to the Dice character himself.

The segment begins as the comic is closing out his set. In the audience, a voice shouts a request for the Mother Goose routine. “No, no,” Dice calmly says, batting away a fly. “Stop with the rhymes. Stop with that already. People are driving me out of my mind with my fucking stupid rhymes.” He continues in this vein, growing more agitated with each word. “I hate the fucking poems,” Dice moans at last. “I wish I never came up with the fucking poems!”

In the darkness of the crowd, a lone voice persists. The comedian sighs. He is America’s ogre in twilight, but at this moment sounds like a pensioner who has received tepid soup at a delicatessen. The room falls silent. “You know, killing for me is like breathing for other people,” Dice quietly boasts. “Don’t do my jokes that are 90 years old. But I run across people like you all the time. And I understand that you appreciate those jokes. So I shouldn’t, like, get aggravated.” Dice pauses—and then gets aggravated, picking up his pace and hardening his tone. Though spontaneous, he speaks with the musicality and mushrooming fury of a Scorsese anti-hero in meltdown. “You sound really stupid when you say it, though. Because you’re not a comic and you don’t know how to say it. You have no delivery, you have no style. But you say it anyway. And you probably say it to your friends and your girlfriend. And they look at you like, ‘Why are you doing it?’ What do I care if you do it? Do I live with you? Do I gotta look at your stupid face every day?”

Off mic, the man is heard protesting. “Why are you bullshitting me?” Dice charges.

“I’m not,” the man says.

With characteristic charm, Dice turns to the man’s date. “Look at her,” he spits, like Rickles gone to the dark side. “With her legs open and her crack out in the air.” Repellent. There is a smattering of uncomfortable laughter. “You think Liz Taylor sits with both her legs up in the air, with her crack out in the air? No!”

The comic and heckler exchange words, and Dice gathers speed. Any attempt to mask the self-loathing behind his rant fails. The Diceman is unraveling. “I would never know a lady, right?” the comedian roars. “Because I’m vulgar. I’m disgusting, right? I say all the dirty words. I could never get someone like you!”

In the audience, the patron objects. Dice goes in for the kill, accelerating his speaking pattern, a boxer pounding an opponent on the ropes. There is an uncanny beauty to his cursing, the rush of obscenities sparkling like midnight American poetry. “You fucking prick cocksucker,” he shouts. “You don’t even get to fuck the chick you brought in here, that’s how fucking stupid you are, cause you got a dick the size of a fucking thumbtack. That’s what I think and that’s what I think of you. I think you like taking it up the ass. I think you like blowing little boys, that’s what I think about you. You’re a prick. I’d like to fucking suck out your eyeballs and skull-fuck you! That’s what I think, okay? Where’s your big comeback now? Huh, tough guy? I’ll push your fucking face through the fucking piano. I’ll make you one of the fucking keys, you motherfucker!”

The heckler attempts a comeback, to which Dice maniacally laughs, like Cesar Romero taunting Adam West. “I fucked your mother in the ass and she had you,” the comic spits. “That’s my jump back. Alright, it’s your turn.”

There is a rumbling in the crowd, leading to some debate about whether the Diceman did, indeed, engage in anal intercourse with the heckler’s mother, thus leading to the man’s conception. Finally, the comedian finishes off the heckler. As if his preceding words—both from this confrontation and the decade on stage that led to it—were not lewd enough, Dice here turns to a version of “the Aristocrats” bit. The joke, which describes intrafamily carnal activities, is a standard of blue comedy: “Summertime” for assholes. Years later, the routine would be dragged into the light of day by Gilbert Gottfried during a legendary Friars Club roast and an ensuing documentary film, The Aristocrats. Not surprisingly, in Dice’s telling, the bit becomes even more indecorous than its seedy norm. “I fucked your mother in the ass, cunt, and mouth,” the comic begins. “How do you like that? And it flowed out of her ears. And then I dipped the head in my asshole, and I’ve got pictures to prove it. I made your grandfather fuck your sister in the fucking asshole while he licked your mother’s asshole, while she was taking a shit on your father—that’s what I did. And your grandmother licked it off his belly and baked it and basted it and then served it to the whole fucking family!”

Dice chuckles to himself, proud of his handiwork. But his unlikely duet has not ended: In the audience, the heckler has stood from his chair, angling to fight the performer. “Don’t stand up,” the comedian charges. “You don’t scare me. You’ll get a foot up your ass before you even get close to me.”

“Yeah, why?” the heckler says. “You don’t scare me.”

“You don’t scare me, tough guy!” the comic replies, menacingly. “Well, come on!”

On the album, we hear what sounds like Dice’s microphone dropping to the floor as he makes his way off stage to charge the heckler. Dice’s words, freed of amplification as he wades into the audience, are suddenly faint. “I’d sit down if I was you,” he says.

“Or what?” cries the heckler.

“I would sit down if I was you,” Dice repeats. “Cause I’ll stick both these glasses up your fucking ass, you motherfucker.”

And that’s it. Just as it began four years prior, the album ends in mysterious silence.

We never learn the outcome of the fight. But we do know what happened to the Diceman: He went belly up, stranded for years in the showbiz wilds. Some contend that “The Argument” hastened his demise. And perhaps that was the comedian’s aim: He certainly does not sound like a happy man. Regardless, never again would Dice be as savage as he appears on The Day the Laughter Died and, especially, its pugnacious finale. A quarter-century hence, it stands as a bravura performance marked by the herculean commitment to character by Andrew Silverstein—the comedian who gave birth to Dice before being swallowed whole by his creation. And as much as we gather to toast Dice, we also must celebrate Silverstein: the nice Jewish boy from a good home in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn; the comic who unleashed his leather-clad id onto the nation’s largest stages; the gifted actor who got lost in his role of a lifetime, never to return.

***

Paul Rubenfeld was born in 1952 and came of age in Sarasota, Florida. He was the eldest child of Milton Rubenfeld, a swashbuckling New Yorker who, after flying for Britain and America during World War II, enlisted in Israel’s clandestine Air Force to join the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. He was one of only five pilots: an Air Force the size of Fleetwood Mac. One fable has Milton, gunned down over Israeli territory and not fluent in Hebrew, shouting “gefilte fish!” to alert the Israelis that he was not an Arab combatant. Despite its microscopic ranks, the Air Force helped sway the war.

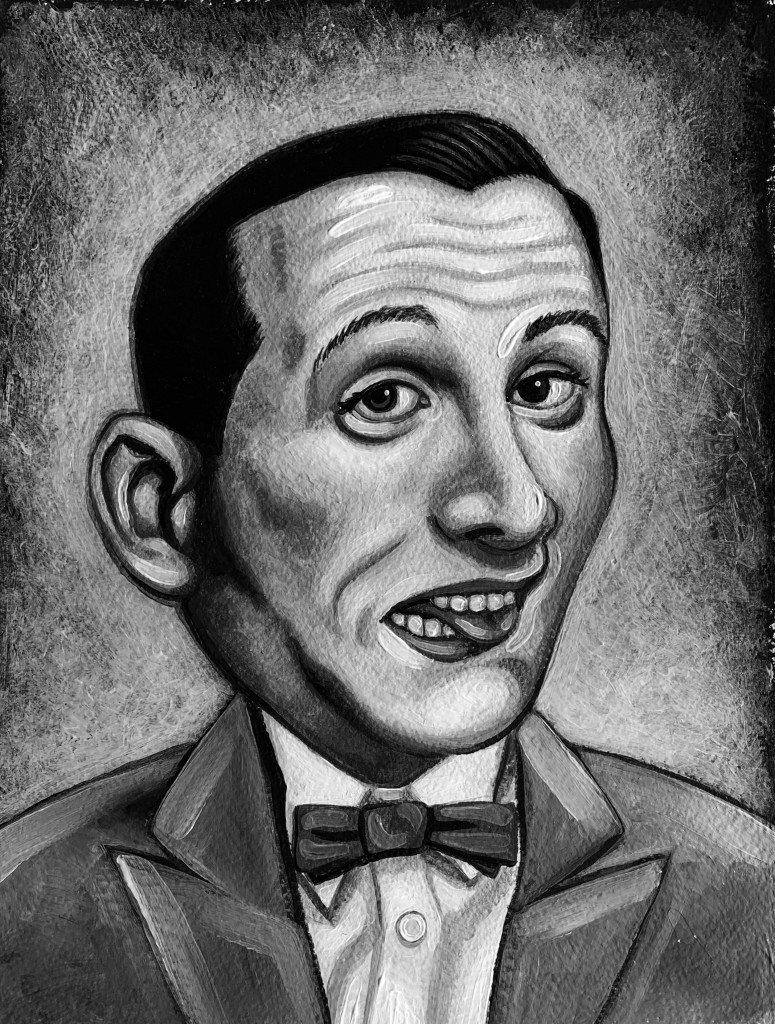

Milton’s son lacked his father’s grit. An aspiring thespian and attendee of circus camp, he cut out for the West Coast after high school, enrolling in CalArts’s outré theater program. Following graduation, he found a performance home in the Groundlings, a nascent Los Angeles improv troupe. He also changed his surname—Rubenfeld seeming unfit for a marquee even in the mid-’70s—to Reubens.

The newly christened actor entered a Los Angeles comedy world with no shortage of titans. Few had the nerve of Andy Kaufman, a child of Great Neck who lived without fear. In death, Kaufman has become synonymous with his elaborate pranks, particularly his controversial tenure as the World Inter-Gender Wrestling Champion. Yet in the mid-’70s, the comedian’s greatest stroke might have been his Elvis Presley impersonation—in particular, the way it would emerge, like a Singapore orchid blooming in Death Valley, from his nebbishy “Foreign Man” character. This rapid pivot from milksop to lothario would recur throughout Kaufman’s career. At one point in the star-making sitcom Taxi, his virginal Latka Gravas becomes afflicted with multiple personality disorder and transforms into Vic Ferrari, a professed aficionado of “Italian cars, Technics stereos, Australian films, and beautiful ladies.” Most enduring was the comedian’s loutish lounge singer Tony Clifton, sexism and cigarettes oozing from beneath his buffoonish moustache.

As with much comedy born in the decade of fern bars and chest hair, Kaufman’s virile characters parodied the cheesy machismo of an awkward era. Yet in his metamorphoses from schlemiel to schmuck, Kaufman was echoing a landmark comedy performance from the previous decade: Jerry Lewis’s 1963 film The Nutty Professor, in which a hapless scientist, Julius Kelp, mutates into the lascivious playboy Buddy Love. Lewis’s movie is a Jewish fantasy, released at a time when Jews were still finding their footing in America. And while it obviously plays on Jekyll and Hyde, The Nutty Professor—like the dyads coursing through Kaufman’s repertoire—seems rooted in a beloved, covertly Semitic figure of Lewis’s adolescence: Superman, that goyish fever dream of Clark Kent and his minders, Siegel and Shuster.

Few figures have overreached with the insecure hysteria of poor Superman, who, to prove his manhood in an adopted land, dons patriotic pajamas and flies through the air battling evil with his fists. From certain angles, the mighty hero seems a colossal loser: The guy who believes he must save planet Earth just to get a date with some shiksa reporter. He is an absurd pipedream of how a mid-century Jew wished Americans might view him—just as Clark Kent, inept to an almost demented degree, represented a Jew’s fear of how he was actually perceived.

Jerry Lewis and Andy Kaufman, generations removed from the immigrant experience but carrying the emotional scars formed over centuries of societal rejection, were riffing on the same themes. Their nebbish characters were preposterously overstated bumblers—sexless and, at times, of indeterminate foreign origin. Their macho foils presented berserk misreadings of American masculinity, unleashed with such hostility (especially in Kaufman’s case) that the comedians’ allegiance with the world’s gentle souls was rarely in doubt.

Into this tradition, in white platform shoes, stepped Paul Reubens, the artistic son of the fighter pilot. In the Groundlings, the young comedian had concocted a pool of characters, including a Native American lounge singer, Chief Jay Longtoe. Yet the bit that caught fire with audiences involved a hyperactive dweeb, resplendent in red bowtie and light-gray glen plaid: Pee-wee Herman, born in a Groundlings revue in 1977.

Kaufman was unusual for a comedian, relishing boos where others chased only laughter. In this sense, Reubens was more characteristic of his species. As Pee-wee triumphed, he shed his other characters. Soon, the comedian had subsumed himself into his nerdy creation: He had Pee-wee headshots, a Pee-wee stage show, and, as his star rose, Pee-wee talk-show appearances. However radical his characters, Andy Kaufman was always Andy Kaufman, master ironist. Paul Reubens quickly became a footnote to Pee-wee Herman. His approach anticipated the unsubtle climate of the ’80s, with its daft burlesques, be they Mr. T or Ronald Reagan. By the time of his breakout movie, the 1985 Tim Burton dazzler Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, Pee-wee Herman was billed as playing “Himself,” and Paul Reubens credited only as a writer. Reubens, né Rubenfeld, had written himself out of existence.

And then, there is Dice. On September 29, 1957, Andrew Clay Silverstein drew his first breath, ogled the labor and delivery nurse, and fumbled about for his cigarettes. He was raised in Brooklyn, a biographical fact about which he is not shy disclosing. His father ran a process-serving agency. In his teens, Silverstein attended James Madison High School, sharing his alma mater with Ruth Bader Ginsburg, William Gaines, and Bernie Sanders—visages for a Jewish Everest.

In 1978, weeks shy of his 21st birthday, Silverstein signed up for amateur night at Pips Comedy Club, a notorious spot in his own Sheepshead Bay neighborhood. At various points in its history, the room had hosted Andy Kaufman, Rodney Dangerfield, Joan Rivers, and Woody Allen. It was known as a tough room, the kind of place where a comedian might get heckled by the bartender. The aspiring comic brought his entire family to watch his set, as if he were a child performing a violin recital. Even Grandma Dice came.

In his youth, Silverstein had entertained his family by impersonating Jerry Lewis. It was as Lewis’s Julius Kelp that Silverstein first greeted the comedy world, walking onstage at Pips in full Nutty Professor regalia. The Brooklyn crowd booed: a nerd! Yet the rookie comedian had an ace up his sleeve. At some point in his act, Silverstein cued the lights and, echoing Kaufman’s transformation into Elvis, reemerged with a well-honed impression of John Travolta, the reigning Italian-American stud, whose Grease had opened in theaters months prior. In interviews about his debut, the comic suggests that his Danny Zuko impression caused an audience pandemonium unseen in the outer boroughs since the Beatles had played Shea. Inflated reminiscence or not, he was soon booked for a headlining slot at Pips, as Andrew Clay. By decade’s end, he had moved to Los Angeles, finding a stage home at Mitzi Shore’s Comedy Store.

According to lore, one night at the Comedy Store in the early ’80s, Silverstein found himself at the club bereft of his Jerry Lewis accouterments. Called onstage, he improvised, clinging to his embryonic “Diceman” character: a prurient jackass with the tacit attributes of an Italian-American. Andrew Dice Clay had entered the building. The comic claims to have adopted the “Dice” sobriquet while leafing through his bar mitzvah photo album and being struck by an image of a classmate playing dice. Yet in the tongue of his adopted people, the Italians, dice means “he says.” And say he did, with depraved splendor.

Just as Paul Reubens had cast aside his non–Pee-wee characters, Silverstein quickly discarded his Nutty Professor routine to pursue stage life as the Diceman. As the ’80s progressed, he took a version of the character to the occasional film or TV role (Pretty in Pink, Diff’rent Strokes) while gradually bringing his standup act to a boil. And as Pee-wee Herman overtook Paul Reubens, Andrew Dice Clay—like the unmanageable monsters created by all those fabled mad scientists—swallowed poor Andrew Silverstein. Buddy Love had sprung to life and spiraled out of control.

Were they inverses or a distorted mirror? Pee-wee the wimp, Dice the barbarian—the comics had cleaved Andy Kaufman in two. Reubens became Foreign Man, Silverstein became Elvis; Reubens embodied Julius Kelp, Silverstein embodied Buddy Love; Reubens was Clark Kent, Silverstein was Superman. One man a schlemiel, the other a schmuck. The aesthetically inclined is constitutionally pulled toward Pee-wee, that camp child of John Waters, crowned with his halo of goodness. The character is aligned with punk rock—born in 1977 itself, months ahead of “Rock Lobster.” Dice, clad in his leather armor and dopey fingerless gloves, comes from cornball hard rock. He’s repugnant, a heel, a repository for the sins of the ’80s. And yet it is Dice I come back to, again and again. Dice, Dice, always Dice.

***

In 2013, when my wife was pregnant with our daughter, floaters began appearing in my left eye. The condition, in which tiny black dots dance across one’s field of vision, is typically harmless, but I figured I might as well get it checked out. “I can’t believe I’m pregnant,” my wife said as I left the apartment, “and you’re the one running to doctors.”

The ophthalmologist examined my eyeball with a glaring light. “I’m glad you came in,” he said. “I want you to go to a retina specialist right away.” An hour later, a new doctor was looking at my eyeball under an even brighter light. She hurried out of the room, darted back in, and asked, “When was the last time you ate?” She explained that a giant tear had developed on my retina and I would need to be operated on—immediately.

Any color remaining in my face after a lifetime of apprehension instantly vanished. “Just laser surgery, right?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “Surgery-surgery. We’re in a race against the clock.”

I was hustled over to the Eye and Ear Infirmary, the mangy hospital on the northern fringe of the East Village, and prepped for surgery. During the operation, somebody asked me if I had children. I dreamily replied that after nearly 15 years as a couple, my wife and I were expecting our first baby. I vaguely recall a nurse saying, “Awww.” It was the first time I had shared our news beyond family.

As part of the procedure, the doctors inserted a gas bubble in my left eye. For several weeks, I was ordered to keep my head facing straight down, night and day. The few times I ventured outside, my wife gingerly led me by the hand as I examined the pavement, like an elderly person who has dropped a $100 bill. My surgeon told me that of his patients, I was a 9 on a seriousness scale of 10. The injury appeared to be random, prompted only by vindictive retinal gods.

As the days crept into weeks, I sat in a special “facedown” chair, suppressing the terror of my predicament, of my future eyesight, and of impending fatherhood. My typical activities—writing, tennis, swimming, bumming around town—were verboten. Mostly, I listened to The Howard Stern Show. I had been a fervent but inconsistent listener since adolescence; now, I clung to the show as a lifeline. Listening in this condition gave me a newfound appreciation for the uncorked and at times wicked humor that I had long adored. When you’re sitting facedown, you do not want NPR niceties. You want an entertainer maniacally committed to retaining his audience’s attention through virtually any means. Such is Stern.

The radio show, already decades old, was at the time entering an unlikely golden period. Subtly at first, then through grander gestures, the host had recalibrated his program, jettisoning the stripper banter that once partially defined him while embracing kinder matters (animal rights, psychotherapy) that a lesser comedian might fear. Through it all, the riotous humor remained, always breathing fire. Stern had outmaneuvered his persona. In my frazzled state, I leaned on this unusual man’s voice, familiar from much of my life but now softened, politically stirred, and somehow funnier than in his alleged heyday. When at last I was permitted to lift up my head and resume normalcy—some vision spared, some lost—I felt indebted to Stern, saved by his enlightened idiocy. But my nerves remained frayed.

Shortly after concluding my facedown purgatory, with the baby’s debut just weeks away, I was cooking dinner while listening to the Stern Show—my nightly ritual. I thrilled at the announcement of that day’s guest: Andrew Dice Clay. The host and guest shared a long and rocky relationship, replete with explosive on-air feuds and reconciliations. Since the early ’90s, as Stern continued his inexorable ascent, Clay had mostly floundered, stranded in the period that for Stern merely served as a launching pad. For a few years, the once-mighty Diceman had seemed to evade the public radar altogether. Now, suddenly, he was back with a bullet: a firecracker appearance in the Woody Allen drama Blue Jasmine.

Dice interviews can be antsy, but that morning he came to Stern stripped of any hostility or façade. The comedian was in full Silverstein mode, gushing endlessly about the rock band fronted by his sons and the films of Allen, his strange bedfellow. He talked Stern through his initial trepidation in taking the film role, largely on account of a medical issue. “I got an eye problem with my left eye,” Dice said. “I haven’t seen out of my left eye for three years….”

In my kitchen, I froze, not trusting my ears. I rewound to listen again. “My retina started detaching,” the comedian was saying. My blood rushed; I pictured the hapless Diceman on his own facedown chair, terrified and pitiable. The comic explained how, following his improbable career resurrection, his doctor marveled at his fortitude. “‘Most people, when they have that kind of problem, what happens is, they fold. They quit their job, they go into this deep depression,’” he claimed the doctor told him. “‘You go the opposite way.’”

When Dice first popped in the late ’80s, I was in the grip of puberty, rightfully terrified of girls. He was the role model beamed to Earth’s surface from the farthest reaches of Hades’s underworld. Now, in my state of distress, he was giving me the pep talk for which I yearned, hovering above me like some foul-mouthed guardian angel.

I saw Blue Jasmine the next day. With its Oscar-sanctified star turn by Cate Blanchett, it likely will be the last Allen movie to win universal acclaim. For Dice, it marked artistic redemption: his greatest performance in 20 years, when “The Argument” concluded The Day the Laughter Died, Part II. Obviously, the Allen film was strictly an acting assignment. Yet Dice’s character—fat, broken, and humbled from life’s daggers—seemed the logical endpoint of the seething beast who stormed offstage two decades prior. Finally, the damaged old Dice I craved.

In the wake of Blue Jasmine, there have been two competing Dicemen. One takes the path of righteousness, surfacing sporadically with nuanced character work in prestige projects such as Bradley Cooper’s A Star Is Born (Dice plays Lady Gaga’s father) and the Scorsese-directed pilot of the ill-starred HBO show Vinyl (his character quickly gets bludgeoned to death). In 2016 and 2017, there was also Dice—the comedian’s very funny, if largely unwatched Showtime series, which suggested a Vegas take on Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Mostly, however, he remains a creature of standup, locked in a watered-down version of his character. Diceman in the present tense is an odd proposition. Those originally touched by his magic do not necessarily want him lingering around; his scorching halt to The Day the Laughter Died, Part II provided too perfect an exit. The dream is that the moment he stomped offstage to physically assault a heckler—the Dice version of riding off into the sunset—his persona expired. We fantasize that, in reality, Dice is an effete British dandy, or Andy Kaufman in disguise, or currently teaching poetry at Bennington. Instead, like a reunited band or rebooted sitcom, he loiters onstage, withering in the spotlight.

As with many active performers still hunting for income, the comedian fails to safeguard his legacy. It deserves better. For a comic of his standing, Dice’s influence can seem minimal—but if you squint, his impact exists. Young male comedians in the Dice mold tend to give me the creeps; his energy lies with women, bawdy broads talking smack onstage. Perhaps the most striking homages have come from a pair of performers working outside of standup. In 2011, Lady Gaga—then still a pop star from the future rather than the past—introduced a short-lived drag persona, Jo Calderone, who liberally cursed and dragged on a cigarette with a familiar flare. Stronger and more subtle is the fireball actress and writer Natasha Lyonne, most explicitly in her mesmeric Netflix series Russian Doll; when, toward the first season’s climax, her character namedrops Dice, it crackles like an atom bomb. In the Andrew Dice Clay biopic that plays in my mind, she is the star.

Russian Doll was unleashed in 2019, the rare hint of the divine poking through a saturated cultural wasteland. Throughout her show, Lyonne maintains an admirable Dice-ian swagger, all external toughness; as the comedy critic Jason Zinoman has noted, she hides inside an overcoat invoking Sam Kinison, Dice’s fallen arch rival. When at last her character invokes the comedian, it is a proclamation of devotion. (She is, per self-description, “a very tough lady who looked like if Andrew Dice Clay and the little girl from Brave made a baby. …And I love Dice.”) Yet like many in our shared demographic, born between Nixon and Reagan, Lyonne is also a child of Pee-wee Herman. In her case, the ancestry is direct: Lyonne debuted at age 6, acting on the madcap morning show Pee-wee’s Playhouse. She played Opal.

We all know how Pee-wee’s Playhouse ended. In 1991, while visiting his war-hero father in Sarasota, Paul Reubens ran afoul of the law by exposing himself at a pornographic movie theater. Strangely, to those familiar with his act, it occurred during a heterosexual film. As the comedian’s Cindy Sherman mug shot—stringy long hair, trashy goatee, theatrical scowl—made the rounds, CBS yanked the show from syndication. Inevitable, perhaps. But by then, production on the show had already ceased. (I have heard murmurs that prior to his arrest, Reubens had been late delivering an episode to the network—a greater sin, in CBS’s hallowed eye, than public indecency.)

Life in character had weighed him down. Indecent exposure was Reubens’s unseemly exit ramp, the decision to zoom down it a secret of his subconscious. Soon after the arrest, Pee-wee rapturously emerged during a MTV broadcast—“Heard any good jokes lately?”—but then went dormant, even as Reubens made sporadic non-Herman appearances. Eventually, Pee-wee was resurrected courtesy of the modern-day algorithm, quick to give audiences what they think they crave. But Pee-wee Herman as a consummate being effectively died masturbating—the eternal boy conclusively reaching puberty, 14 years after his birth, in one final blaze of mischief.

Even children might recognize Pee-wee Herman as a persona. With Dice, the distinction was never so clear. In his 1993 book Private Parts, Stern recounts taking the comedian house-hunting in Long Island and recoiling as Dice—accompanied by an assistant named “Hot Tub Johnny”—cursed, smoked, and dished out insults. “I can’t believe he really talks like Dice, all the time!” Stern writes. “People who knew him early on told me that he didn’t talk like that, but I think he’s actually become that guy.”

Had Dice really ossified in character, transforming into what he had set out to mock? It’s hardly an unprecedented sensation. The Beastie Boys have long claimed that, in the wake of Licensed to Ill, they briefly fell into a similar trap, arguably set by the group’s producer and label boss, Rick Rubin. The Beastie Boys parted with the producer in 1988—just around the time that Dice, in some ways their darker replacement, joined Rubin’s stable.

As well-bred New Yorkers in possession of a solid artistic foundation and sharp media instincts, the Beastie Boys had the wherewithal to wiggle free of their prescribed characters. It was a maneuver that Dice never managed—though he did try. In 1995, not long after the comedian’s stage meltdown concluded The Day the Laughter Died, CBS debuted the sitcom Bless This House. It starred one “Andrew Clay” as a harried family man and postal worker. A promotional still portrayed the star on the receiving end of a noogie, administered by his character’s wife. When the sitcom perished after its lone season, the comic retreated, reinserting the demonic “Dice” into his name. The public only had use for him as a heel.

Years before she slipped off the deep end, Roseanne Barr claimed that Dice was “a Jewish guy seeing a non-Jewish world.” It is tempting to dismiss her words—paranoid racial rambling from nutty Roseanne, spoken in an age when Jews hardly qualify as the American underclass. But I cannot shake her quote. I think she meant that the Dice character is forever overreaching—like an overeager Ralph Lauren sweater that aspires to WASP gentility but tips into farce. Or piteous Superman, zooming through the sky in his vain attempt to fit in. The shock of Dice’s act was that such a vast audience accepted him at face value. Oh, well. At least he never set his sights on the presidency. Because this certainly wouldn’t be the last time a macho grotesque would slither out of New York, an obvious joke to all but the lowliest yokel, only to be embraced by the masses.

I never ceased listening to The Day the Laughter Died albums, particularly “The Argument.” Even now, when standup specials often flirt with the experimental, the records remain uniquely odd and ferocious. But sometimes I wonder whether the albums’ intimacy grossly misrepresents Dice, especially when compared to the Madison Square Garden material that I so scorned. After all, the comedian’s ultimate punch line—nastier than anything concocted by Andy Kaufman, Howard Stern, or even Sacha Baron Cohen—was nothing that tumbled from his locker-room lips. It was the stadium full of imbeciles, gleefully cheering the Diceman’s every deranged word.

***

Years ago, I attended standup shows with admirable regularity. For a few thrilling months, I even caught my favorite comedian, Joan Rivers, every week of her club residency downtown, as if I were a hippie and Joan the Grateful Dead. Throughout the years, however, I studiously avoided witnessing Dice perform, wary of puncturing the mystique.

But I did once see him. It was 2014, and his autobiography, The Filthy Truth, was newly published. An errand had called me to the east side—I think it involved a cable box—and it occurred to me that Dice was scheduled for a book signing at a Barnes & Noble along my route. How, as a clear-headed citizen of the world, could I possibly miss it?

As I waded through the city, a parade was gearing up. Veterans Day? Something like that. But as I walked, I became fixated on the idea that the barricades and crowds had descended upon Manhattan for Dice. I passed the Waldorf-Astoria and envisioned the comedian inside, daintily slipping into his fingerless gloves. Within, a butler was entering a lavish suite’s boudoir and interrupting the comedian’s reverie. “Mr. Dice, the procession will depart shortly,” he might announce. “Your memoir signing looms.” Nearing the bookstore, I considered approaching a policeman to inquire about the stalled traffic. But I knew what he would say: “Sorry, bub—the Diceman’s in town. You know how it is.”

By the time I reached the Barnes & Noble, I was giddy from my delusion, bracing for pandemonium. But to enter the bookstore was to hear the abrupt skid of a record needle. For there were no delirious hordes; there were just pockets of middle-aged Andrew Dice Clay enthusiasts, tucked away upstairs. The men exuded a nervous energy: No doubt, for many, it was their first time inside a bookstore that lacked a neon sign. I joined the group, feeling a little embarrassed to be among their shiftless ranks.

But then, suddenly, there he was…Dice! It was really Dice! Trudging through the store, a heavenly gleam radiating off his pate. Watch him go, dripping chutzpah in his wake, a human cartoon. And his identity was unequivocal. He was Andrew Silverstein. He was Andrew Dice Clay. He was the most vulgar, vicious comic ever to walk the face of the earth, and he was approaching the dais.