The Summer of Dark Helmet: Stalking Mel Brooks

[Article and illustration from Lowbrow Reader #10, 2017]

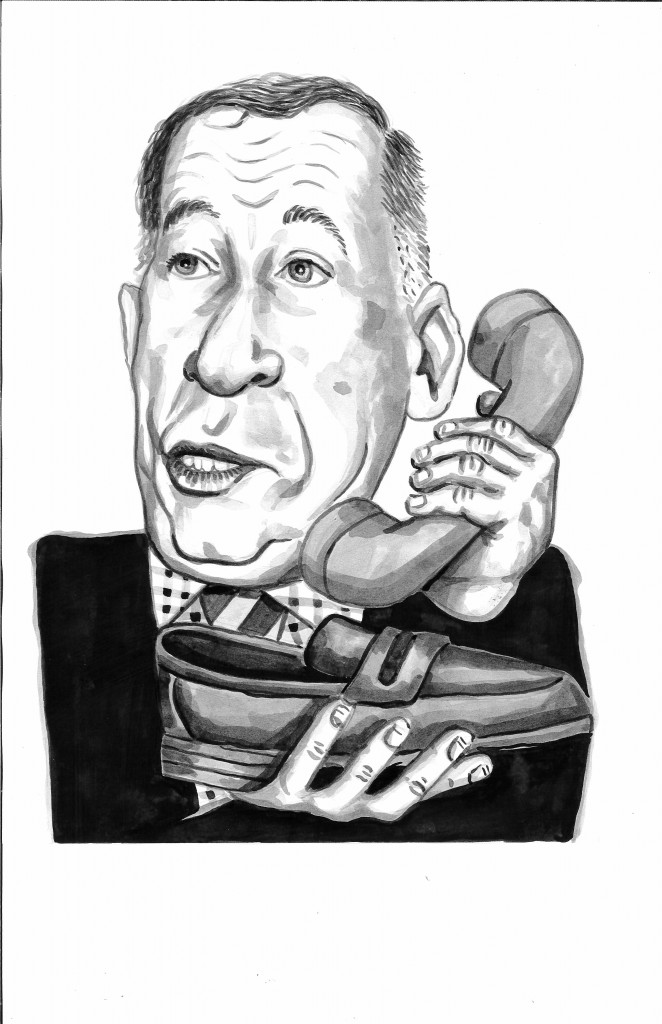

The glories of Mel Brooks are best represented by his decades-running 2000 Year Old Man conversations with Carl Reiner. They are found in his cult favorite The Twelve Chairs and much ballyhooed Producers musical, in his early work on Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows and the talk show appearances he makes as a senior citizen. Most of all, they become manifest in his trifecta of collaborations with Gene Wilder: The Producers, Young Frankenstein, and—let us now bow our heads and fart—Blazing Saddles.

Yet to many who spent their childhoods tucked away in milquetoast suburbs across Reagan’s America, the Brooksian myth first flickers with Spaceballs, his effervescent Star Wars spoof from 1987, four years after Jedi. The reasons for such a generational awakening are curious: The movie’s creator, while regarded as film royalty, was by then over 60. It had been about six years since his previous box office hit, History of the World, Part 1. Meanwhile, David and Jerry Zucker’s partnership with Jim Abrahams fortified a stronghold in zany fare, having mocked the ’70s disaster genre (Airplane!),’60s spy craze (Top Secret!), and kidnapping noir (the raunchy, Disney-backed Ruthless People).

You have to wonder why Abrahams and the Zucker brothers used such antiquated milieus as platforms for hijinks. I’m not knocking them. Trapping dozens of civilians on a pilotless Boeing 707 is a perfectly adequate setting for a little girl to insist that her coffee assume the same complexion as that of her lovers—but why not capture the imaginations of a generation while you’re at it? Hone your radars closer to relevancy and drive a stake into the biggest franchise going.

So for me, it all started with Spaceballs. It was June, the month of the film’s theatrical release. School was out. Mom took me to a theater, now defunct, behind a shopping mall. There, for the first time, we witnessed Dr. Schlotkin’s threat to reverse Princess Vespa’s sweet-sixteen rhinoplasty and Colonel Sandurz’s walking in on his boss playing with his dolls again.

My father must have been at work. He was a buyer for my family’s retail chain, Larry’s Shoes, named after my maternal grandfather. In the early ’70s, Dad started working for his father-in-law’s business, a reputable men’s footwear chain founded inside a tin shack in 1949. It specialized in first-rate service (albeit from a pushy commission-based sales staff) and an incredible selection of hard-to-find sizes. (Chewbacca’s Peter Mayhew and plenty of NBA’s pituitary giants became regular clientele.) Larry’s frowned upon the lazy clerking style of department store staffers, at whom customers barked sizes, sending employees to retrieve Rockports and wingtips without so much as bending a knee.

Larry’s was a proud operation. It kept generations of family together, for good or ill, and Dad made a decent salary. We wouldn’t travel, nor were we members of any country club (though I challenge you to find a Jewish household in 1980’s Fort Worth, Texas, that was), but we had cable TV. We would eat at Chili’s on a typical Friday night, and my brother and I had our own phone line. I cannot remember exactly when Southwestern Bell installed 817-763-9258, but I do know that it happened before Mom and Dad separated. When they sat us down at the kitchen table to explain, it was handled respectably and calmly. After the conversation, I ran to my room to dial Myles, my best friend and cousin. His parents had split years earlier. If anyone my age would have the answer on how to deal when your father asks your mother for a “time out,” Myles would know. “Look on the bright side,” my cousin reassured me. “You’ll get two separate Hanukkahs.”

***

A belching Pizza the Hutt and the infinite Spaceball One at “ludicrous speed,” along with whatever else I was able to comprehend during those 96 minutes back in 1987, was more than enough to sell me on finding out more about Mel Brooks. What other movies was this sweet, silly wise-ass responsible for? Why was his name ablaze in light-saber blue credits with the other stars? I knew of Rick Moranis, John Candy, and Joan Rivers. But who was this Brooks, the Jew responsible for all the anarchy? In the car on the way home from the theater, Mom turned her head to me and smiled. “You know, Brian, you should really see Blazing Saddles.”

At some point, Mom and I also obtained Young Frankenstein and History of the World, Part 1. Maybe we watched High Anxiety, too? I wouldn’t get around to The Producers and The Twelve Chairs until much later. But what I had already seen that month convinced me that I had discovered the messiah of toilet humor. I wanted to be closer to him, maybe even meet him! I couldn’t put my finger on why, nor did I have any idea how. But I had the spare hours and separate phone line to figure it out.

This was during a time long before technological conveniences ruined the art of stalking. If you wanted to find someone’s contact in another city, or so I learned, you would need to dial the area code followed by 555-1212. It seemed like the kind of thing an idiot would have on his luggage. Soon after, I asked information for the number to Brooksfilms and gave it a ring so that I could get its address.

Writing to the studio for Brooks’s autograph was likely my mother’s suggestion. When else had I collected the signature of a famous person? The response was, by any era’s snail-mail standards, more than efficient. A package awaited me one afternoon, weeks later and near the end of summer. It contained a signed glossy diptych of President Skroob and Yogurt. “To Brian, Best Wishes, Mel Brooks.” This wasn’t a Xerox. No question, Mel hand-signed it. Accompanying the photograph was a poster and a vinyl copy of Spaceballs: The Soundtrack, featuring the Spinners’s title theme, the Pointer Sisters’s “Hot Together,” and Van Halen’s “Good Enough.” The soundtrack was autographed in metallic silver Sharpie: “All the Best, Mel Brooks.”

Again, it was his penmanship. He took time out to do it, which meant that must have been some letter I wrote, or maybe Mel was just a sincere and good-hearted person who valued any admiration thrown his way. But well-intentioned as he may have been, Mel created a monster. Days (or a half-hour) after receiving the Spaceballs paraphernalia, I called Brooksfilms again. Mel’s assistant picked up. She was polite and articulate; for whatever reason, I have it engrained in my memory that she was Asian.

“Hello, may I please speak to Mel Brooks?”

The assistant offered the standard brush-off and sent me on my way. Worth a try, I thought. Who knows, maybe he sat around waiting for strange children from out of state to rain praise upon him. More than likely, he was attempting negotiations for Moranis’s pay on the never-realized Spaceballs sequel or plotting Life Stinks, his upcoming musical about the homeless. Or maybe he was still doing press for Spaceballs. Theatrical runs back then lasted for months, after all, and when I returned to school—when everybody who was anybody was still laughing about being surrounded by Assholes—I wasn’t worried about Mel’s schedule. Or my own homework, for that matter. I’m not certain how aware my mother was of my trigger-happy dialing hand. But Brooksfilms most likely was, as the besieged assistant fell victim to my pestering daily.

“Hello, may I please speak to Mel Brooks?”

“Hello, may I please speak to Mel Brooks?”

“Hello, may I please speak to Mel Brooks?”

“Young man,” she relented as the week was nearing its end, “would you like to make an appointment?”

An appointment! Yeah, that’s what I wanted. Whatever the hell that was. The fact that this assumed Asian had the autonomy to schedule her boss to phone a grubby eight-year-old in another time zone is telling. (Aren’t these sorts of gestures generally reserved, if at all, for morning talk shows to capitalize on folksy publicity?) Before I hung up, a time was confirmed. I ran into the kitchen, where Mom was finishing one of her Vantage Ultra Light 100s and on the phone with a friend, likely venting about marriage-counseling sessions. “Mel Brooks is calling my line on Friday at 2pm,” I said. We calculated that it meant 4pm my time. Mom also began to calculate the monthly AT&T bill. But she didn’t care. This was a family event not to be missed.

When I got home from school that day—September 11, 1987—my grandparents were already lingering in the hallway. To witness their grandson take a call from Mel Brooks, I suppose, was like observing a secular bar mitzvah. The phone rang in my room.

“Hello?”

“Hello, Brian?” Mel asked in that distinct raspy Brooklyn accent.

“Mr. Brooks?” I lifted up out of my chair a bit.

“Brian, this is long-distance. This costs money. Does your mother know you’re calling?”

She knew. She was the one prodding me to ask for a visit to the studio, plus a photo of him when he was a little pisher running around Depression-era Williamsburg. The director declined both requests. Whether his “nos” had been accompanied by polite laughter, I cannot recall. There wasn’t much else I can remember that he told me, only the feeling of his graciousness throughout the conversation and the fact that he thanked me when I informed him that my favorite movie was Blazing Saddles. Before we had both hung up, Mom had a couple of other notes scribbled on a loose sheet of legal paper placed in front of me. “Ask him for his shoe size,” she whispered. The following month, my father had black Footjoy lizard loafers, size 9 Charlie, delivered to Mel’s post office box in Beverly Hills.

My grandfather had not expected to pick up the tab for sending a pair of exotic dress shoes to the 2000 Year Old Man, especially since he was already giving Mom a boost during the separation. My dad wasn’t there that day. The divorce wouldn’t finalize for another year, but visitation was already agreed upon—5 to 8pm on Wednesdays, plus alternate weekends. I always went, and Dad certainly played some role in all of this. At the very least, he’s in part responsible for enabling his two sons’ juvenile sensibilities. Obviously, his moving out factored into my need to connect with Mel—who, in addition to his comforting father-figure image and clear appreciation for merchandising, shared an identical height and similar head of cropped gray hair with my grandfather (and, OK, every other Ashkenazi alter kocker in the Western Hemisphere). Nobody in the family read much into it. My behavior had not caused alarm or prompted the need to psychoanalyze for a possible fragile emotional void. Understandably, everyone had their priorities. There were shoes to sell and phone bills to pay. Also, someone needed to drop those Footjoys in the mail, a subject about which Dad and Brooks shared a brief correspondence.

There is a letter framed on my wall, dated November 13, 1987, in which Mel thanked my father for the expensive footwear. “The shoes are beautiful,” it read. “I wore them last Saturday night and got many compliments. I told everybody all about Brian and his generous Father and Grandfather.” Inside a pocket on the picture frame’s back dust cover is a Polaroid of the shoes, taken by my father.

***

I continued to watch Brooks’s movies, of course, and whatever essentials Dad would dub on a VHS timer when I would visit on weekends. A few years later, the film obsession was put on pause when I fell in love with the family business and joined the sales team at Larry’s Shoes. Around the same time, my father was fired. I’ll spare you the details, only that it was a personal conflict between him and my uncle, who, coincidentally, began to groom me. He jokingly characterized me as the Andy Garcia to his Al Pacino in The Godfather, Part III. It was only a matter of time to master the business and take it over, though that would require a higher education. My father, even as a Larry’s ex-pat, couldn’t agree more about college, but I was stubborn. I wanted to make money and gain confidence, meet girls and learn how to dress—not the most destructive plan, as far as a 19-year-old guy’s plans go, but still a problem.

Dreams of spending the rest of my life in the shoe biz evaporated around 2001. By that time, I was a manager at one of the stores. I possessed exceptionally good leadership skills, according to the HR director, but exceptionally poor administrative skills. After an administrative blunder, I was suspended for a few months and demoted to sales associate; nothing felt the same. I just wanted a job that could be fun. So I went to a junior college, started writing for a local alt-weekly, and began to carve my way into some kind of career related to writing about movies.

Within a few years, the family business had gone bankrupt, and I found myself working at Heeb magazine in New York City. One of my primary responsibilities at the magazine was wrangling celebrities for photo shoots. Mel Brooks was to Heeb what Mick Jagger is to Rolling Stone, or Jesus Christ to Christianity Today. To say that his name came up for possible coverage would be an understatement. Yet the circumstances were different. A young assistant picked up the line and was understandably standoffish. The office had no email, she explained. Brooks didn’t even keep a computer. He planned on retiring in the next five years. There would be no interview, and I had no more loafers to offer.

—Lowbrow Reader #10, 2017