When Rickles Sings

[Article and illustration from Lowbrow Reader #7, 2009, and The Lowbrow Reader Reader book, 2012.]

Don Rickles fans—what a sour lot! Front-row masochists and back-of-the-room cowards, Rat Pack fetishists and young men intrigued with old Vegas, nasty uncreative types prowling for put-downs and men’s magazine subscribers with a misplaced sense of the ironic.

And yet Don Rickles himself—what a guy! He’s curmudgeonly and cute, a wrinkly Yoda with an attitude problem. Deep into his 80s, he remains one of the world’s quickest talk-show guests. (Chris Rock, the reigning champion of the couch, credits Rickles with drawing his blueprint.) He is world famous as an “insult comic” and yet is a notoriously kindhearted soul. He’s an improbable unifier: the man who allegedly doesn’t like anybody, liked by everybody.

Last fall, Rickles headlined three nights at New York’s Town Hall. This was the same stage show captured in John Landis’s documentary Mr. Warmth: The Don Rickles Project, but somehow it seemed far stranger in person. The show is embalmed in time. A bald singer opens with a Frank Sinatra tribute. “I’m just a guy from Brooklyn,” he says, “and here I am, at Town Hall.” Rickles wears a tux, putters about the stage like a Florida retiree searching for his keys. In an age of solitary comics, he performs in front of an orchestra. Toward the end of the show, he introduces the VIPs scattered around the audience—Paul Shaffer! Cedric the Entertainer! Regis!—and insults them. He cracks jokes informed by Greatest Generation stereotypes, slanty-eyed Orientals and the like, but he holds no bile. When I saw Jackie Mason a few months earlier, his bigotry seemed genuine and ugly, as if his every summer weekend had been ruined by the stupidity of Polacks and sloth of schvartzes; Rickles delivers his slurs so lovingly, they seem like compliments. When he dies, the comic will be halted at the gates of heaven by awed gods, eagerly awaiting their insults.

A few years ago, I briefly spoke with Rickles by phone. (He was giving me a quote about another comedian, who I was profiling for a magazine.) Rickles greeted me with a gentle, somewhat obligatory insult; then the rancor melted away, revealing a warm and soft-spoken old man. His act follows a similar pattern. He frontloads the insults, his calling card. Even given his repute, the comic can seem shockingly cruel—but what are people thinking being overweight, or of German descent, or comely, or old, and attending a Don Rickles performance? As the show wears on and his glass empties, the comedian turns increasingly to the maudlin. Night after night, tears well in his eyes as he salutes his late mother (he is a notorious mama’s boy); he gives a hokey spiel about the worth of friends and toasts Sinatra, under whose spell he remains. And then, in the night’s most berserk portion, Rickles fires up the orchestra and sings.

Only a lunatic would attend a Don Rickles show for the music. Nonetheless, night after night, the comic weaves in and out of these songs that nobody wants to hear. Like many standups, he sings with natural flow and big personality, his voice trembling and sweet. Next to Rickles, Joan Baez seems insincere and Thom Yorke lighthearted. Yet his music’s earnestness is no more a front than his comedy’s wrath: Rickles was molded in an age that predated the cultural saturation of unblinking irony. It is difficult to imagine callous-minded comedians of subsequent generations breaking into heartfelt song. At the same time, none of these heirs are as merciless as their savage elder. Herein lies the magic of Rickles’s songs: They are windows to his vulnerability and thus his license to kill. They reinforce the true punch line to the comedian’s “Mr. Warmth” moniker—its veracity—while granting this nice old man permission to unleash his ferocious hoard of million-dollar insults.

—Lowbrow Reader #7, 2009 (The article also appears in our book, The Lowbrow Reader Reader.)

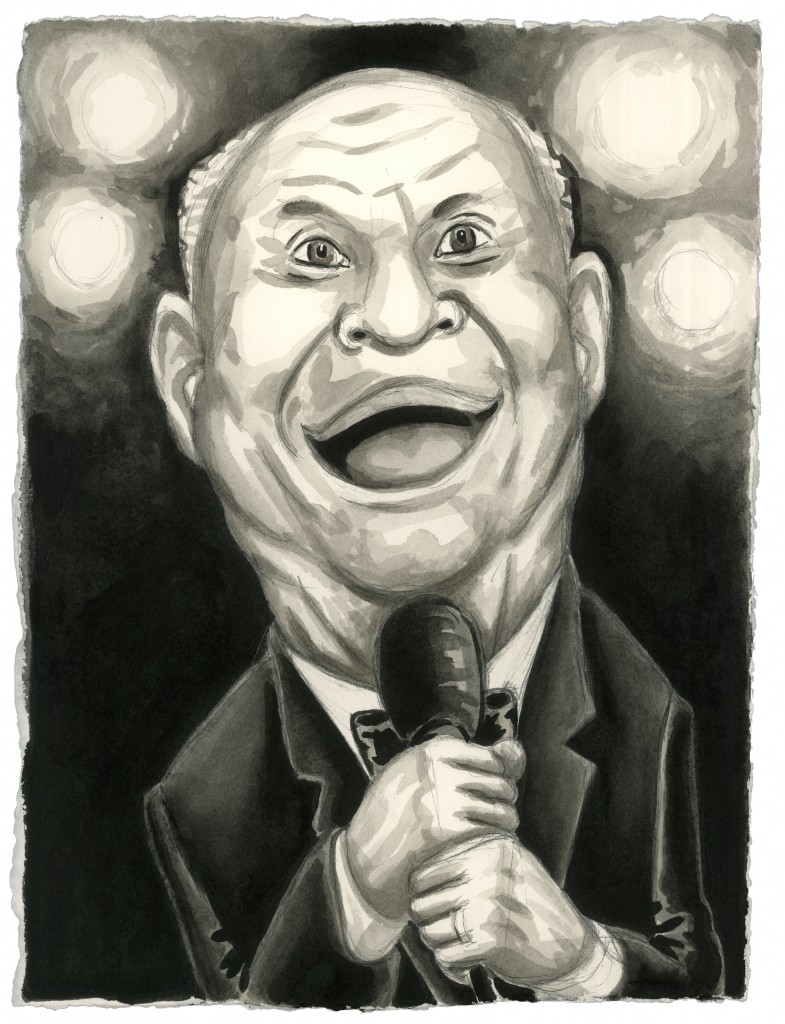

Illustration by Tom Sanford